Note: this article required conversations with a lot of people. A (hopefully) exhaustive, randomized list of everyone whose thoughts contributed to the article: Lachlan Munroe (Head of Automation at DTU Biosustain), Max Hodak (CEO of Science, former founder of Transcriptic), D.J. Kleinbaum (CEO of Emerald Cloud Labs), Keoni Gandall (former founder of Trilobio), Cristian Ponce (CEO of Tetsuwan Scientific), Brontë Kolar (CEO of Zeon Systems), Jason Kelly (CEO of Ginkgo Bioworks), Jun Axup Penman (COO of E11 Bio), Nish Bhat (current VC, ex-Color CEO), Amulya Garimella (MIT PhD student), Shelby Newsad (VC at Compound), Michelle Lee (CEO of Medra), Charles Yang (Fellow at Renaissance Philanthropy), Chase Armer (Columbia PhD student), Ben Ray (current founder, ex-Retro Biosciences automation engineer), and Jake Feala (startup creation at Flagship Pioneering).

Introduction

I have never worked in a wet lab. The closest I’ve come to it was during my first semester of undergrad, when I spent 4 months in a neurostimulation group. Every morning at 9AM, I would wake up, walk to the lab, and jam a wire into a surgically implanted port on a rat’s brain, which was connected to a ring of metal wrapped around its vagus nerve, and deposit it into a Skinner box, where the creature was forced to discriminate between a dozen different sounds for several hours while the aforementioned nerve was zapped. This, allegedly, was not painful to the rat, but they did not seem pleased with their situation. My tenure at the lab officially ended when an unusually squirmy rat ripped the whole port system out of its skull while I was trying to plug it in.

Despite how horrible the experience was, I cannot in good conscience equate it to True wet lab work, since my experience taught me none of the lingo regularly employed on the r/labrats subreddit.

I mention my lack of background context entirely because it has had some unfortunate consequences on my ability to understand the broader field of lab automation. Specifically, that it is incredibly easy for me to get taken for a ride.

This is not true for many other areas of biology. I have, by now, built some of the mental scaffolding necessary for me to reject the more grandiose claims spouted by people in neurotechnology, toxicology prediction, small molecule benchmarks, and more. But lab robotics eludes me, because to understand lab robotics, you need to understand what actually happens in a lab—the literal physical movements and the way the instruments are handled and how materials are stored and everything else—and I do not actually understand what happens in a lab.

Without this embodied knowledge, I am essentially a rube at a county fair, dazzled by any carnival barker who promises me that their magic box can do everything and anything. People show me robots whirling around, and immediately my eyes fill up with light, my mouth agape. To my credit, I recognize that I am a rube. So, despite how impressive it all looks, I have shied away from offering my own opinion on it.

This essay is my attempt to fix this, and to provide to you an explanation of the heuristics I have gained from talking to many people in this space. It isn’t comprehensive! But it does cover at least some of the dominant strains of thought I see roaming around in the domain experts of the world.

Heuristics for lab robotics

There are box robots, and there are arm robots

This is going to be an obvious section, but there is some groundwork I’d like to lay for myself to refer back to throughout the rest of this essay. You can safely skip this part if you are already vaguely familiar with lab automation as a field.

In the world of automation, there exist boxes. Boxes have been around for a very, very long time and could be considered ‘mature technology’. Our ancient ancestors relied on them heavily, and they have become a staple of many, many labs.

For one example of a box, consider a ‘liquid handler’. The purpose of a liquid handler is to move liquid from one place to another. It is meant to take 2 microliters from this tube and put it in that well, and then to take 50 microliters from these 96 wells and distribute them across those 384 wells, and to do this fourteen-thousand times perfectly, which is something that humans eventually get bored with doing manually. They must be programmed for each of these tasks, which is a bit of a pain, but once the script is written, it can run forever, (mostly) flawlessly.

Here is an image of a liquid handler you may find in a few labs, a $40,000-$100,000 machine colloquially referred to as a ‘Hamilton’.

Why do this at all? Liquids are awfully important in biology. Consider a simple drug screening experiment: you have a library of 10,000 compounds, and you want to know which ones kill cancer cells. Each compound needs to be added to a well containing cells, at multiple concentrations, let’s say eight concentrations per compound to generate a dose-response curve. That’s 80,000 wells. Each well needs to receive exactly between 1 and 8 microliters of compound solution, then incubate for 48 hours, then receive 10 microliters of a viability reagent (something to measure if a cell is alive or dead), then incubate for another 4 hours, then get read by a plate reader. If you pipette 11 microliters into well number 47,832, your dose-response curve for that compound is wrong, and you might advance a false positive, or even worse, miss a drug candidate.

Difficult! Hence why automation may be useful here.

Many other types of boxes exist. Autostainers for immunohistochemistry, which take tissue sections and run them through precisely timed washes and antibody incubations that would otherwise require a grad student to stand at a bench for six hours. Plate readers, often used within liquid handlers, measure absorbance or fluorescence or luminescence across hundreds of wells. And so on.

Boxes, which can contain boxes within themselves, represent a clean slice of a lab workflow, a cross-section of something that could be parameterized—that is, the explicit definition of the space of acceptable inputs, the steps, the tolerances, and the failure modes of a particular wet-lab task. Around this careful delineation, a box was constructed, and only this explicit parameterization may run within the box. And many companies create boxes! There are Hamiltons, created by a company called Hamilton, but there are boxes made by Beckman Coulter, Tecan, Agilent, Thermo Fisher, Opentrons, and likely many others; which is all to say, the box ecosystem is mature, consolidated, and deeply boring.

But for all the hours saved by boxes, there is a problem with them. And it is the unfortunate fact that they, ultimately, are closed off from the rest of the universe. A liquid handler does not know that an incubator exists, a plate reader has no concept of where the plates it reads come from. Each box is an island, a blind idiot, entirely unaware of its immediate surroundings.

This is all well and good, but much like how Baumol’s cost disease dictates that the productivity of a symphony orchestra is bottlenecked by the parts that cannot be automated—you cannot play a Beethoven string quartet any faster than Beethoven intended, no matter how efficient your ticketing system becomes— similarly, the productivity of an ‘automated lab’ is bottlenecked by the parts that remain manual. A Hamilton can pipette at superhuman speed, but if a grad student still has to walk the plate from the Hamilton to the incubator, the lab’s throughput is limited by how fast the grad student can walk. An actual experiment is not a single box, but a sequence of boxes, and someone or something must move material between them.

Now, you could add in extra parts to the box, infinitely expanding it to the size of a small building, but entering Rube-Goldberg-territory has some issues, in that you have created a new system whose failure modes are the combinatorial explosion of every individual box’s failure modes.

A brilliant idea may occur to you: could we connect the boxes? This way, each box remains at least somewhat independent. How could the connection occur? Perhaps link them together with some kind of robotic intermediary—a mechanical grad student—that shuttles plates from one island to the next, opening doors and loading decks and doing all the mindless physical labor? And you know, if you really think about it, the whole grad student is not needed. Their torso and legs and head are all extraneous to the task at hand. Perhaps all we need are their arms, severed cleanly at the shoulder, mounted on a rail, and programmed to do the repetitive physical tasks that constitute the majority of logistical lab work.

And with this, we have independently invented the ‘arm’ line of lab robotics research. This has its own terminology: when you connect multiple boxes together with arm(s) and some scheduling software, the resulting system is often called a “workcell.”

As it turns out, while only one field benefits from stuff like liquid handlers existing—the life-sciences—a great deal of other fields also have a need for arms. So, while the onus has been on our field to develop boxes, arms benefit from the combined R&D efforts of automotive manufacturing, warehouse logistics, semiconductor fabs, food processing, and any other industry where the task is “pick up thing, move thing, put down thing.” This is good news! It means the underlying hardware—the motors, the joints, the control systems—is being refined at a scale and pace that the life sciences alone could never justify.

Let’s consider one arm that is used fairly often in the lab automation space: the UR5, made by a company called Universal Robots. It has six degrees of freedom, a reach of about 850 millimeters, a payload capacity of five kilograms, and costs somewhere in the range of $25,000 to $35,000. Here is a picture of one:

Upon giving this arm the grippers necessary to hold a pipette, to pick up a plate, and to click buttons, as well as the ability to switch between them, your mind may go wild with imagination.

What could such a machine do?

Arms within boxes? Wheels to the platform that the robot is mounted upon, allowing it to work with multiple boxes at once? So much is possible! You could have it roll up to an incubator, open the door, retrieve a plate, wheel over to the liquid handler, load it, wait for the protocol to finish, unload it, wheel over to the plate reader, and so on, all night long, while you sleep and dream. This is the future, made manifest.

Well, maybe. If this were all true, why are there humans in a lab at all? Why haven’t we outsourced everything to these cute robotic arms and a bunch of boxes?

Most lab protocols can be automated, they just often aren’t worth automating

If you were to speak to LLM’s about the subject of lab robotics, you will find that they are pretty pessimistic on the whole business, mostly because of how annoying the underlying machines are to use. I believed them! Especially because it does match up with what I’ve seen. For example, there is a somewhat funny phenomenon that has repeated across the labs of the heavily-funded biology startups I’ve visited: they have some immense liquid handler box lying around, I express amazement at how cool those things are, and my tour guide shrugs and says nobody really uses that thing.

But as was the case in an earlier essay I wrote about why pathologists are loathe to use digital pathology software, the truth is a bit complicated.

First, I will explain, over the course of a very large paragraph, what it means to work with a liquid handler. You can skip it if you already understand it.

First, you must define your protocol. This involves specifying every single operation you want the machine to perform: aspirate 5 microliters from position A1, move to position B1, dispense, return for the next tip. If you are using Hamilton’s Venus software, you pipette from seq_source to seq_destination, and you must do something akin to this for every container in your system. Second, you must define your liquid classes. A liquid class is a set of parameters that tells the robot how to physically handle a particular liquid: the aspiration speed, the dispense speed, the delay after aspiration, the blow-out volume, the retract speed, and a dozen other settings that must be tuned to the specific rheological properties of whatever you’re pipetting. Water is easy, glycerol is apparently really hard, and you will discover where your specific liquid lies on this spectrum as you go through the extremely trial-and-error testing process. Third, and finally, you must deal with the actual physical setup. The deck layout must be defined precisely. Every plate, reservoir, and tip rack must be assigned to a specific position, and those positions must match reality. The dimensions of the wells, the height of the rim, the volume all must be accurately detailed in the software. If you’re using plates from a different supplier than the one in the default library, you may need to create custom labware definitions.

And at any point, the machine may still fail, because a pipette tip failed to be picked up, the liquid detection meter threw a false negative, something clogged, or whatever else.

To help you navigate this perilous journey, Hamilton, in their infinite grace, offers seminars to teach you how to use this machine, and it only costs between 3,500 and 5,000 dollars.

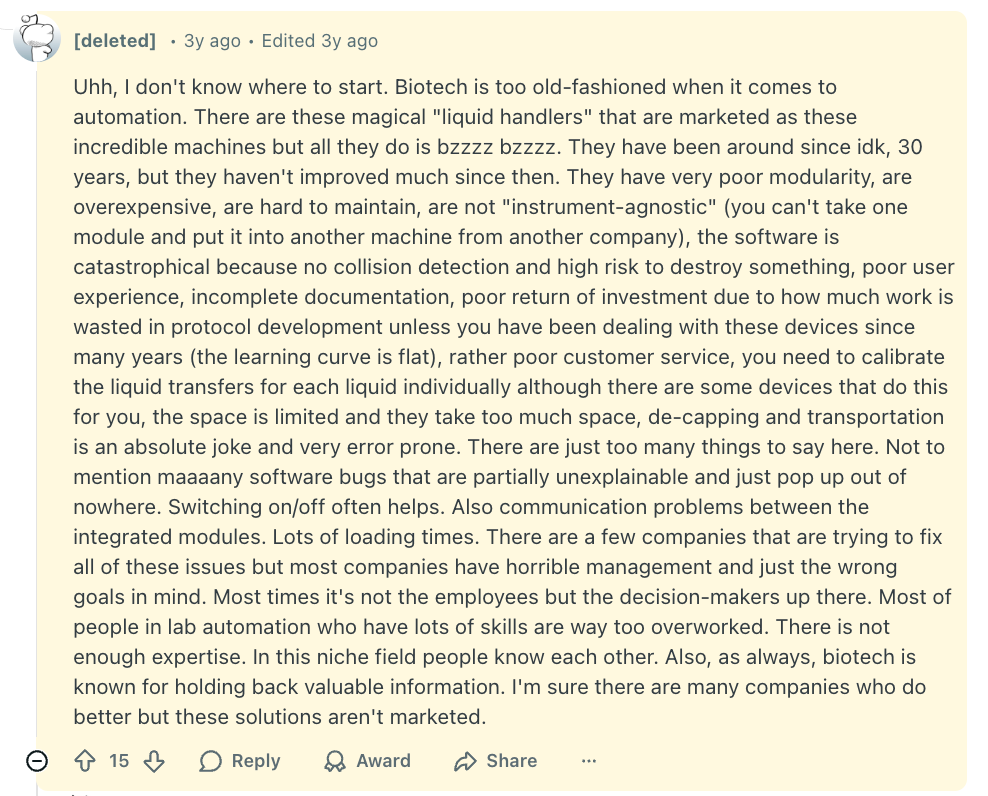

And here’s a Reddit post with some more details:

Now, yes, this is annoying, especially if you compare it with manual pipetting. There, a trained researcher picks up a pipette, aspirates the liquid, watches it enter the tip, adjusts instinctively if something seems off, dispenses into the destination well, and moves on. The whole operation takes perhaps fifteen seconds. Perhaps the researcher gets really bored with this and doesn’t move particularly fast, but if you assemble enough of them together and call it graduate school or an RA position, you can scale things up quite a bit without needing to touch a robot at all. Oftentimes, that may not only be the more efficacious option, but also the cheaper one.

But there is a very interesting nuance here: if the task is worth automating, it actually isn’t that big of a deal to automate.

From talking to automation engineers, there is a distinct feeling I get that if we had an infinite number of them (and scientists to let them know their requirements) worming through our labs, there is a very real possibility that nearly everything in an average wet-lab could be automated. After all, there are centrifuges, incubators, and so on that are all automation compatible! And the engineers I talked to don’t actually mind the finicky process of tuning their boxes and arms that much. Yes, dialing in a protocol can be tough, but it is often a ‘solvable over a few hours’ problem. In the edge case of dealing with genuinely strange protocols that bear little resemblance to what the automation engineer has seen before, it could take perhaps weeks, but that’s it.

So what’s the problem?

Most protocols simply aren’t run enough times to justify the upfront investment.

Let’s assume it takes an automation engineer forty hours to fully dial in a new protocol, which is a reasonable estimate for something moderately complex. At a loaded cost of, say, $100 per hour for the engineer’s time, that’s $4,000 just to get the thing working. Now, if you’re going to run this protocol the exact same way ten thousand times over the next month, that $4,000 amortizes to forty cents per run. Trivial! Also, it’d probably be nearly impossible to do via human labor alone anyway, so automate away. But if you’re going to run it fifty times? That’s $80 per run in setup costs alone, and then you might as well just have a human do it.

This is, obviously, an immense oversimplification. Even if a wet-lab task could be ‘automated’, most boxes/arms still need to be babysat a little bit. But still! The split between robot-easy problems and robot-hard problems—in the eyes of automation engineers—has a lot less to do with specific motions/actions/protocols, and a lot more to do with ‘I will run this many times’ versus ‘I will run this once’.

And most protocols in most labs fall into the latter category. Research is, by its nature, exploratory. You run an experiment, you look at the results, you realize you need to change something, you run a different experiment. Some labs do indeed run their work in a very ‘robot-shaped’ way, where the bulk of their work is literally just ‘screening X against Y’, and writing a paper about the results. They can happily automate everything, because even if some small thing about their work changes, it’s all roughly similar enough to, say, whatever their prior assumptions on liquid classes in their liquid handler was.

But plenty of groups do not operate this way, maybe because they are doing such a vast variety of different experiments, or because their work is iterative and the protocol they’re running this week bears only passing resemblance to the protocol they’ll be running next week, or some other reason.

So, how do you improve this? How can we arrive at an automation-maxed world?

You can improve lab robotics by improving the translation layer, the hardware layer, or the intelligence layer

The answer is very obvious to those working in the space: we must reduce the activation energy needed to interface with robotic systems. But, while everybody seems to mostly agree with this, people differ in their theory of change of how such a future may come about. After talking to a dozen-plus people, there seem to be three ideological camps, each proposing their own solution.

But before moving on, I’d like to preemptively clarify something. To help explain each of the ideologies, I will name companies that feel like they fall underneath that ideology, and those categorizations are slightly tortured. In truth, they all slightly merge and mix and wobble into one another. While they seem philosophically aligned in the camp I put them in, you should remember that I am really trying to overlay a clean map on a very messy territory.

The first camp is the simplest fix: create better translation layers between what the human wants and what the machine is capable of doing. In other words, being able to automatically convert a protocol made for an intelligent human with hands and eyes and common sense, into something that a very nimble, but very dumb, robot can conceivably do. In other words, the automation engineer needn’t spend forty hours figuring this out, but maybe an hour, or maybe even just a minute.

This is an opinion shared by three startups of note: Synthace, Briefly Bio, and Tetsuwan Scientific.

Synthace, founded in London in 2011, was perhaps the earliest to take this seriously. They built Antha, which is essentially device-agnostic programming language, which is to say, a protocol written in Antha runs on a Hamilton or a Tecan or a Gilson without modification, because the abstraction layer handles the translation. You drag and drop your workflow together, the system figures out the liquid classes and deck layouts, and you go home while the robot pipettes.

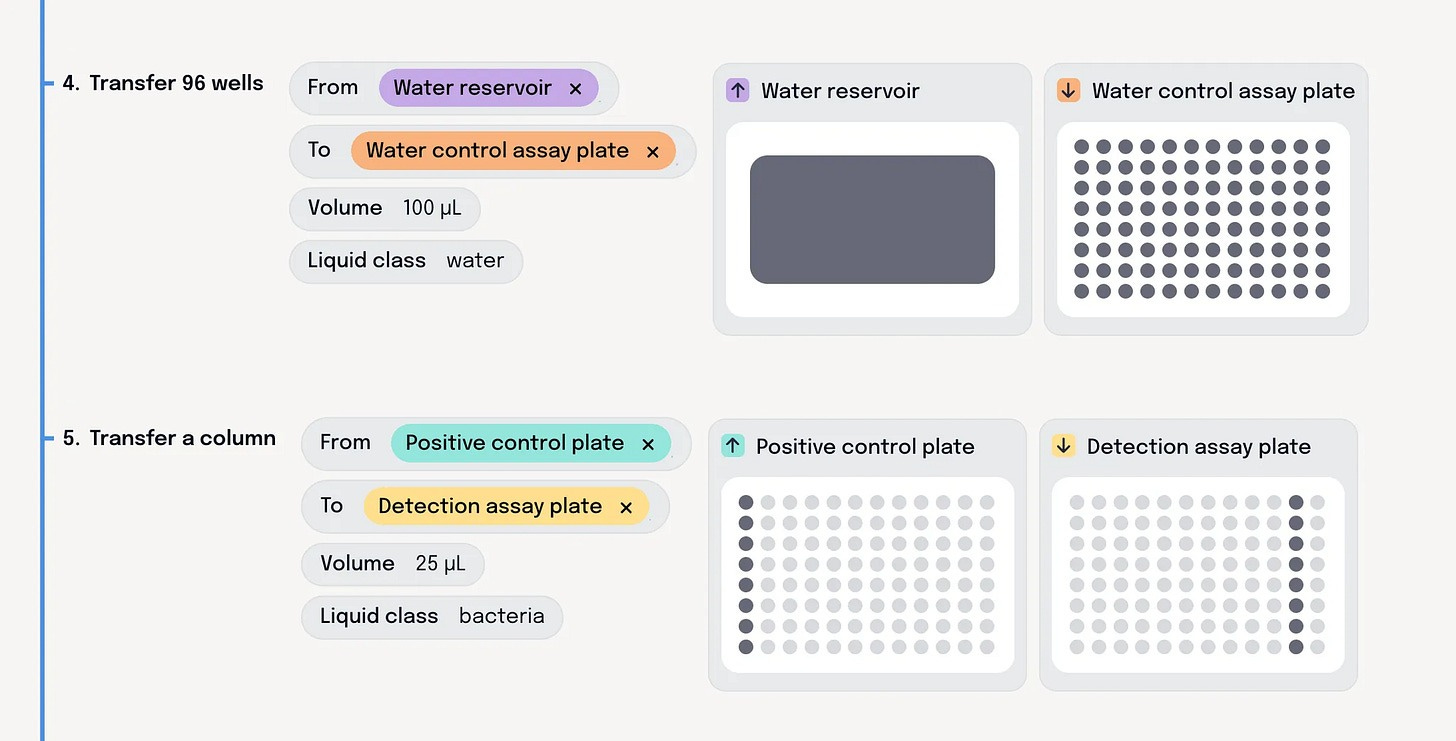

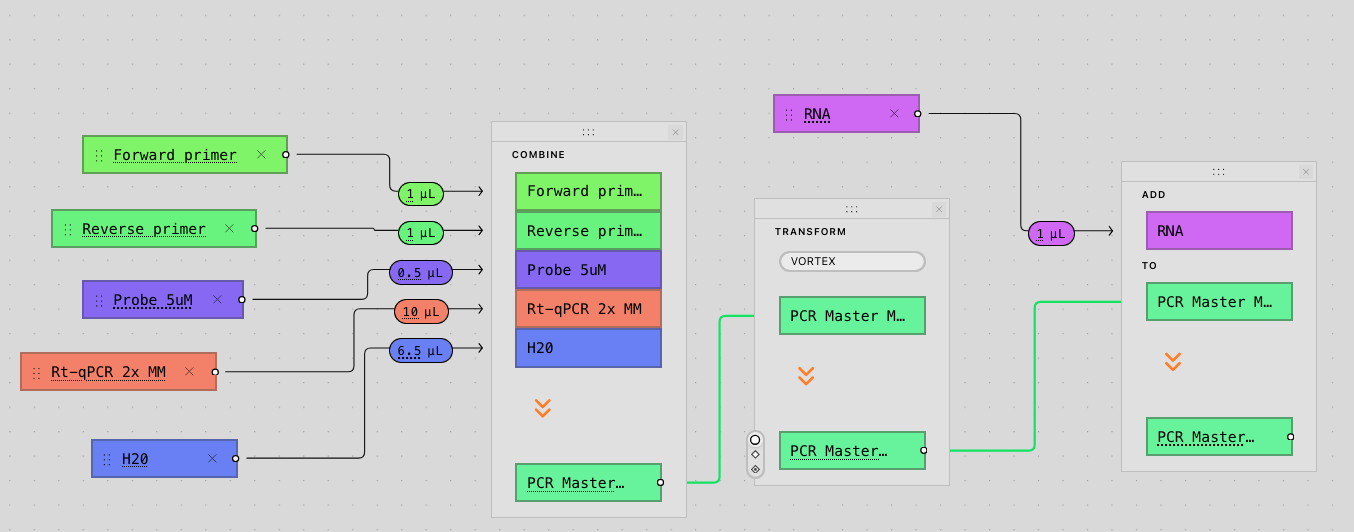

Briefly Bio, which launched in mid-2024 and has perhaps one of the best and least-known-about blogs I’ve seen from a startup, initially started not as a translation layer between the scientist and the robot, but between the scientist and the automation engineer. Their software uses LLMs to convert the natural-language protocols that scientists can write—with all their implicit assumptions and missing parameters and things-that-must-be-filled-in—into structured, consistent formats that an automation team can work with. But since then, the team has expanded their purview to allow these auto-generated protocols (and edits made upon them) to be directly run on arbitrary boxes and arms, alongside a validation check to ensure that the protocol is actually physically possible.

Tetsuwan is the newest of the trio, announced at the end of 2024, and operates at a higher level of abstraction than Briefly and Synthace. Users do not write commands for transfers between plates, instead, they define experiments via describing high level actions such as combining reagents or applying transformations like centrifugations. Then they specify what their samples, variables, conditions and controls are for that specific run. From this intent-level description, Tetsuwan fully compiles to robot-ready code, automatically making all the difficult downstream process engineering decisions including mastermixing, volume scaling, dead volume, plate layouts, labware, scheduling, and liquid handling strategies. The result of this is fully editable by the scientist overseeing the process, allowing them to specify their preferences on costs, speed, and accuracy trade-offs.

And that’s the first camp.

The second camp also admits that the translation layer must be improved, but believes that physical infrastructure will be an important part of that. This is a strange category, because I don’t view this camp as building fundamentally novel boxes or arms, like, say, Unicorn Bio, but rather building out the physically tangible [stuff] that stitches existing boxes and arms together into something greater than the sum of their parts.

The ethos of this philosophy can be best viewed by what two particular companies have built: Automata and Ginkgo Bioworks.

Automata is slightly confusing, but here is my best attempt to explain what they do: they are a vertically-integrated-lab-automation-platform-consisting-of-modular-robotic-benches-and-a-scheduling-engine-and-a-data-backend-as-a-service business. They also call the physical implementation of this service the ‘LINQ bench’, and it is designed to mirror the size and shape of traditional lab benches, such that it can be dropped into existing lab spaces without major renovation. It robotically connects instruments using a robot arm and a transport layer, with them building a magnetic levitation system for high-speed multi-directional transport of plates across the bench. And the software onboard these systems handles workflow creation, scheduling, error handling, and data management. I found one of their case studies here quite enlightening in figuring out what exactly they do for their clients.

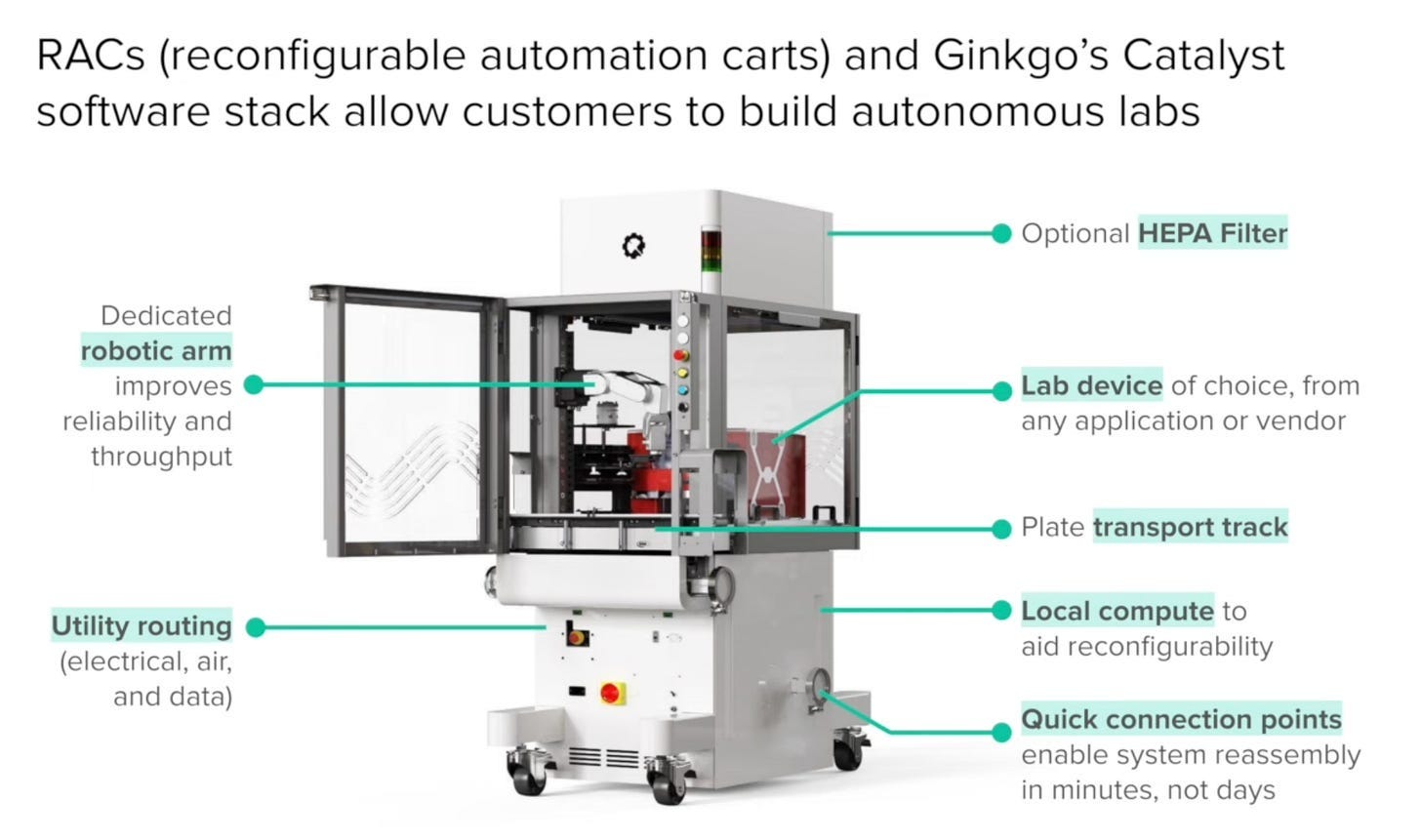

And of course, Ginkgo. Yes, Ginkgo is a mild memetic allergen to those familiar with its prior history, but I do encourage you to watch their 2026 JPM presentation over their recent push into automation. It’s quite good! The purpose of the presentation is to push Ginkgo’s lab automation solution—Reconfigurable Automation Carts, or RAC’s—but serves as a decent view into the pain points of building better lab automation. What are RAC’s anyway? Basically a big, modular, standardized cart that can have boxes (+other things) inserted in, and has an arm directly installed:

There is software that comes onboard to help you use the machines (Catalyst), but their primary focus seems to be hardware-centric.

This is Ginkgo’s primary automation play, though both the RAC’s and scheduling software were really first created by Zymergen, who Ginkgo acquired. And, just the other day, they demonstrated this hardware-centricity by partnering with OpenAI to run an autonomous lab experiment: 36,000 conditions across six iterative cycles, optimizing cell-free protein synthesis costs.

Moreover, the RAC’s each include a transport rack, making it so they can be daisy-chained together in case you need multiple instruments to run your particular experiment.

And that’s the second camp.

The third and final camp believes the future lies in augmenting the existing systems with a greater degree of intelligence. This differs from the translation camp in that the translation camp is primarily concerned with the input side of the problem—converting human intent into robot-legible instructions before execution begins—while the intelligence camp is concerned with what happens during execution.

This is the newest group, and there are two companies here that feel most relevant: Medra and Zeon Systems.

Medra is the oldest player here, founded in 2022, raising 63 million dollars in the years since. Their pitch is that you already have the arms, you already have the boxes, and both are quite good at what they do. Really, what you need most is intelligence. Yes, perhaps the translation layers that the first camp is building, but the Medra pitch is a bit more all-encompassing than that. Onboard robotic intelligence would not only make it easier to do translation, but also error recovery, adaptation to novel situations, ability to interface with arbitrary machines (even ones that are meant to be worked manually), autonomously optimize protocols, design its own experiments outright, and generally handle the thousand small variations that make lab work so resistant to typical, more brittle automation.

Zeon Systems is our final company, and is fundamentally quite similar to Medra, but with a quirk that I find very endearing: their use of intelligence is not necessarily to make robots more capable, but to make them more forgiving. In 2014, Opentrons started, attempting to democratize automation by making the hardware cheap, but cheap hardware comes with cheap hardware problems—tips that don’t seat properly, positioning that drifts, calibration that goes wonky. The Zeon bet is that sufficiently good perception and intelligence can compensate for these shortcomings. If the robot can see that the tip didn’t seat properly and adjust accordingly, you no longer need the tip to seat properly every time. If the robot can detect that its positioning is off and correct in real-time, you no longer need precision machining to sub-millimeter tolerances. Intelligence, in this framing, is not a way to make robots do more, but rather a way to get away with worse machinery. And worse machinery means cheaper machinery, which means more labs can afford to automate, which means more Zeon products (whether that takes the form of software or software + hardware) can be sold.

Okay, that’s that. Those are the three camps.

Now the obvious question: which one of them is correct?

The most nuanced take is: all of them. It feels at least somewhat obvious that all possible futures will eventually demand something of all of these camps, and the companies that thrive will be those that correctly identify which layer is the binding constraint for which customer at which moment in time.

But here is a more opinionated take on each one:

The translation layer camp, to my eyes, has the most honest relationship with this problem. They are not promising to make robots smarter or to sell you better hardware, they are instead promising to make the existing robots easier to talk to, such that the activation energy required to automate a protocol drops low enough that even infrequently-run experiments become viable candidates. If we accept that this problem of protocol building is actually the real fundamental bottleneck to increasing the scale of automation, we should also trust the Tetsuwan/Synthase/Briefly’s of the world to have the best solutions.

You can imagine a pretty easy failure case here is that frontier-model LLM’s get infinitely better, negating any need for the custom harnesses these groups are building, slurping up any market demand that they would otherwise have. To be clear, I don’t really believe this will happen, for the same reason I think Exa and Clay will stick around for awhile; these tools are complicated, building complicated tools requires focus, and frontier model labs are not focused on these particular use-cases. And importantly, many of the problems that constitute translation are solved best through deterministic means (deck & plate layouts, choosing liquid class parameters, pipetting strategies, math of volume calculations). Opus 8 or whatever may be great and an important part of the translation solution, but it probably should not be used as a calculator.

The hardware camp is curious, because, you know, it doesn’t actually make a lot of sense if the goal is ‘democratizing lab automation’. Automata’s LINQ benches and Ginkgo’s RACs are expensive—extremely expensive!—vertically-integrated systems. They make automation better for orgs that have already crossed the volume threshold where automation makes sense. But they don’t actually lower that threshold, nor add in new capabilities that the prior systems couldn’t do. If anything, they raise it! You need even more throughput to justify the capital expenditure! So, what, have they taken the wrong bet entirely? I think to a certain form of purist, yes.

But consider the customer base these companies are actually chasing. Automata and Ginkgo alike are pitching their solutions to large pharma and industrial biotech groups. In other words, the primary people they are selling to are not scrappy academic labs, but rather organizations running thousands of experiments per week, with automation teams already on staff, who have already crossed the volume threshold years ago. Their problem has long gone past ‘should we automate?’, and has now entered the territory of “how can we partner with a trusted institutional consultant to scale to even larger degrees?“. To those folks, LINQ and RAC’s may make a lot of sense! But there is an interesting argument that, in the long term, these may end up performing the democratization of automation in a roundabout way. We’ll discuss that a bit more in the next section.

Finally, the intelligence camp. We can be honest with each other: it has a certain luster. It is appealing to believe that a heavy dose of intelligence is All You Need. In fact, visiting the Medra office earlier this year to observe their robots dancing around was the catalyst I needed to sit down and finish this article. Because how insane is it that a robotic arm can swish something out of a centrifuge, pop it into a plate, open the cap, and transfer it to another vial? Maybe not insane at all, maybe that’s actually fully within the purview of robotics to easily do, but that’s what the article was meant to discover. But after having talked to as many people as I have, I have arrived at a more granular view than “intelligence good” or “intelligence premature.”. There are really two versions of the intelligence thesis. The near-term version is about perception and error recovery: the robot sees that a tip didn’t seat properly and adjusts, detects that its positioning has drifted and corrects in real-time, recognizes that an aspiration failed and retries before the whole run is ruined. This feels quite close! The far-term version is something grander, where you can trust the robot to handle every step of the process, where you show a robot a video of a grad student performing a protocol and it just does it, perhaps even optimizing it, maybe even designing its own experiments—the intelligence onboard granting the robot all the necessary awareness and dexterity to complete anything and everything.

This future may well come! It is not an unreasonable bet. But, from my conversations, it does seem quite far away. Yes, it is easy to look at the results Physical Intelligence are producing and conclude that things are close to being solved, but lab work is very out-of-distribution to what most of these robotics foundation models are learning (and what they have learned is often still insufficient for their own, simpler folding-laundry-y tasks!). I want to be careful not to overstate this, since this greater intelligence may arrive faster than anyone suspects, so perhaps this take will be out of date within the year.

And wait! Wait! Before you take any of the above three paragraphs as a statement on companies rather than philosophies, you should recall what I said in the second paragraph of this section: none of these companies, many of whom the founders I talked to for this article, are so dogmatic as to be entirely translation/hardware/intelligence-pilled. They may lean that direction in the revealed preferences of how their companies operate, but they are sympathetic to each camp, and nearly all of them have plans to eventually play in sandboxes other than the ones they currently occupy.

Speaking of, how are any of these companies making money?

All roads lead to Transcriptic

There is a phenomenon in evolutionary biology called carcinization, which refers to the fact that nature keeps accidentally inventing crabs. Hermit crabs, king crabs, porcelain crabs; many of these are not closely related to each other at all, and yet they all independently stumbled into the same body plan, because apparently being shaped like a crab is such an unreasonably good idea that evolution cannot help itself. It just keeps doing it. I propose to you that there is a nearly identical phenomenon occurring in lab robotics, where every startup, regardless of what its thesis is, will slowly, inexorably, converge onto the same form.

Becoming Transcriptic.

Transcriptic was founded in 2012 by Max Hodak (yes, the same Max who co-founded Neuralink, and then later Science Corp). The pitch of the company was simple: we’ll build out a facility stuffed with boxes and arms and software to integrate them all, and invite customers to interact with them through a web interface, specify experiments in a structured format, and somewhere in a facility, the lab will autonomously execute your will (alongside humans to pick up the slack). In other words, a ‘cloud lab’.

The upside is that the sales pitch basically encompasses the entirety of the wet-lab market: don’t set up your own lab, just rent out the instruments in ours! And with sufficiently good automation, and software to use that automation, the TAM of this is a superset of a CRO.

The obvious downside is that doing this well is really, really hard. Transcriptic later merged with the automated microscopy startup ‘3Scan’, which rebranded as ‘Strateos’, which folded in 2023. This tells us something about the difficulty of this model. This said, Emerald Cloud Labs (ECL) is a startup that appeared two years after Transcriptic with similar product offerings, and they’ve held out, with a steady 170~ employees over the past two years. Yet, while they ostensibly are a cloud lab, they are not the platonic ideal of one in the same way Transcriptic was, in that anyone and everyone can simply log in, and run whatever experiment they’d like; ECL’s interface is gate-kept by a contact page.

Despite the empirical difficulty of making it work, it feels like going down the Transcriptic path is the logical conclusion of nearly any sufficiently good lab automation play.

Why?

Here, I shall refer to ‘Synbio25’, a wonderful essay by Keoni Gandall that I highly recommend you read in full. In this essay, Keoni discusses many things, but what I find most interesting is his comment on the immense economic efficiencies gained by batching experiments:

Robots, in biotechnology, are shamefully underutilized. Go visit some biology labs — academic, industrial, or startup — and you are sure to see robots just sitting there, doing nothing, collecting dust….

The benefit of aggregating many experiments together in a centralized facility is that we can keep robots busy. Even if you just want to run 1 protocol, there may be 95 others who want to run that 1 protocol as well — together, you can fill 1 robot’s workspace optimally. A centralized system lets you do this among many protocols — otherwise, you’d need to ship samples between labs, which is just too much. While the final step, testing your particular hypothesis, might still require customized attention and dedicated robot time, the heavy lifting — strain prep, validation, etc — can be batched and automated.

And one paragraph that I really think is worth marinating in (bolding by me):

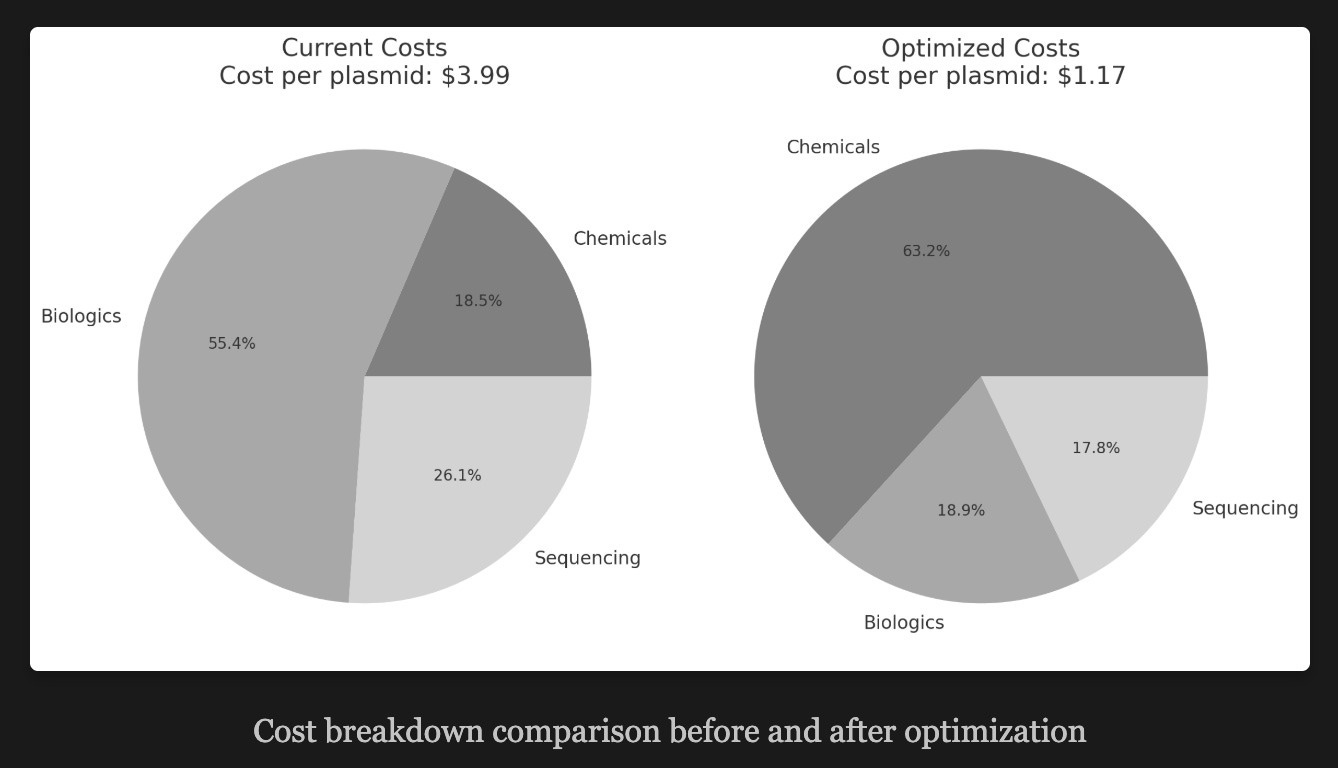

The key, then, is to pull these robots towards projects and protocols that are closer and closer to the raw material side of biology, so that you can build everything else on top of those. For example, PCR enzyme, polymerase, is very widely used, but rather expensive if you buy proprietary enzymes. On the other hand, you can produce it for yourself very cheaply. If you utilize your robots to produce enzymes, you can then use this enzyme in all other experiments, dropping the costs of those experiments as well. The reason is quite simple: without a middleman, your costs approach chemical + energy + labor costs. A billion years of evolution made this, relative to other industries, very inexpensive. You just need to start from the bottom and move up.

There is a very neat logical train that arises from this!

If you are to accept that lab centralization (as in, cloud labs) means you can most efficiently use lab robotics—which feels like a pretty uncontroversial argument—it also means that the further you lean into this, the more able you are to vertically integrate upstream. If you’re running enough experiments such that your robots are constantly humming, you can justify producing your own reagents. If you’re producing your own reagents, your per-experiment costs drop. If your per-experiment costs drop, you can offer lower prices. If you offer lower prices, you attract more demand. If you attract more demand, your robots stay even busier. If your robots stay even busier, you can justify producing even more of your own inputs. And so on, ad infinitum, until you devour the entirety of the market, and the game of biology becomes extraordinarily cheap and easy for everyone to play in.

As an example, the Synbio25 essay offered this picture showing the plasmid production cost differences between unoptimized and optimized settings (read: producing enzymes + cells in-house and using maximum-sized sequencing flow cells). Over twice as cheap!

How dogmatic am I being here? Surely there are other business models that could work.

Perhaps for the next decade! But on a long-enough time horizon, it does feel like eventually everything becomes a cloud lab. Nothing else besides this really seems to work, or, if they do, their upside is ultimately capped and not ‘venture-scalable’, which is to say they may work, but you better not take any money to make it happen. Selling software means you’re easy to clone, being a CRO means you’re ultimately offering a subset of services that a cloud-lab can, and automation consulting has limited upsides. The best potential alternative on the table is to become a Thermo-Fisher-esque entity, selling boxes and arms and reagents to those who want to keep things in-house. But how many of those will there realistically be? How many holdouts could possibly remain as the cloud labs get more and more trustable, all while the business of biotech becomes (probably) more and more economically challenging, making it so justifying your own lab expenses become ever-more difficult?

But how things shake out in the short-term may be different. Because while Transcriptic doesn’t exist today, Emerald Cloud Labs does! And yet, they aren’t necessarily a juggernaut. As of today, we exist in a sort of purgatory, mid-way state, where neither the capability nor the trust to fully rely entirely on cloud labs yet exists. But it is coming. You can see it on the horizon. And so the interesting question to ask is: who stands to benefit the most from the wave in the coming years?

And here is where the hardware camp’s bet becomes a lot more convincing in retrospect. Yes, Automata and Ginkgo are selling expensive hardware systems to large pharma. But you can see the inklings of at least Ginkgo attempting lab centralization themselves by dogfooding their own machines to sell data to customers. Right now, it is functionally a CRO, with a menu of options. But what comes next? I don’t personally know how much easier RAC’s are to set-up for high-mix (read: highly heterogeneous lab experimentation), but the general sense I get from people is that they are. And if that’s true, then the Ginkgo play starts to look less like “we are selling expensive hardware to pharma” and more like “we are building the infrastructure that will eventually become the dominant cloud lab, and we’re getting pharma to pay for the R&D in the meantime.” Which is, if you squint, actually quite clever. Will they pull it off? I don’t know! Something similar for Automata could be said as well; the institution who gathered up a decades-worth of information on how automation is practically used may be well-poised to eventually operate their own cloud lab, having already learned—on someone else’s dime—exactly where the workflows break down and how to fix them.

How about the other groups? What can the intelligence and translation layer groups do during this interim period?

There’s a lot of possibilities. The simplest one is to get acquired. If the endgame is cloud labs, and cloud labs need both intelligence and translation layers to function, then the most straightforward path for these startups is to build something valuable enough that a cloud-lab-in-waiting (like Ginkgo or Automata themselves) decides to buy them rather than build it themselves. Similarly, these startups could become the picks-and-shovels provider that every cloud lab depends on.

But you could imagine more ambitious futures here too. Remember: you can just buy the hardware. Ginkgo’s RACs, Hamilton’s liquid handlers—none of this is proprietary in a way that prevents a sufficiently well-capitalized would-be-cloud lab from simply buying or even making it themselves. The hardware is a commodity, or at least it’s becoming one. What’s not a commodity is the intelligence to run it and the translation layer to make it accessible. So you could tell a story where the hardware companies win the short-term battle—racking up revenue, raising money, building out their systems—only to lose the long-term war to translation/intelligence groups who buy their hardware off the shelf and differentiate on software instead.

Of course, the steelman here is that the hardware companies could simply use their revenue advantage to build the software themselves.

We’ll see what happens in the end. Smarter people than me are in the arena, figuring it out, and I am very curious to see where they arrive.

This section is long, but we have one last important question to ask: why did the first generation of cloud labs not do so well? Was it merely a technological problem? Were they simply too early? This is unlikely according to the automation engineers I talked to; there aren’t massive differences between the machinery back then, and the machinery today. Could blame be placed on the translation layer that these companies had? It doesn’t seem like it; using Transcriptic, as documented in a 2016 blog post by Brian Naughton to create a protein using their service, doesn’t seem so terrible.

What else could be the issue?

There is one pitch offered by Shelby Newsad that I found interesting. The problem is not that these companies were too early, but rather that they were simply too general, and because they were too general, they could never actually make any single workflow frictionless enough to matter.

In the comments of that post made by Shelby, the same Keoni we referenced earlier explained what it was actually like to use a cloud lab (Transcriptic): you had to buy your own polymerase from New England Biolabs, ship it to their facility, pay for tube conversion, and then implement whatever cloning and sequencing pipeline you wanted to run. By the time you’d coordinated all of this, you might as well have just done it yourself. The automation was there! The robots were ready! But because Transcriptic had attempted the ‘AWS for biotech’ strategy right out of the gate, they offloaded the logistical headaches to the user. There is also a side note on how fixing issues with your experiment was annoying, as Brian Naughton states in his blog post: ‘debugging protocols remotely is difficult and can be expensive — especially differentiating between your bugs and Transcriptic’s bugs.’

Delighting the customer is important! Compare this to Plasmidsaurus. They (mostly) do one thing: plasmid DNA sequencing. You mail them a tube, they sequence it, you get results. That’s it, no coordination needed on your end, the entire logistics stack is their problem. And it has led to them utterly dominating that market, and slowly expanding their way to RNA-seq, metagenomics, and AAV sequencing. In fact, if we’re being especially galaxy-brained: there is a very real possibility that none of the companies we’ve discussed so far end up ushering in the cloud labs of the future, and instead, that prize shall be awarded to Plasmidsaurus and other, Plasmidsaurus-shaped CROs, expanding one vertical at a time.

Either way, this reframes the earlier question of which camp will win. Perhaps it’s not just about translation layers versus hardware versus intelligence. It’s about who can solve the logistics problem for a set of high-value workflows, and then use that beachhead to expand.

Conclusion

This field is incredibly fascinating, and the future of it intersects with a lot of interesting anxieties. China is devouring our preclinical lunch, will lab robotics help? The frontier lab models are getting exponentially better, will lab robotics take advantage of that progress to perform autonomous science? Both of these, and more, are worthy of several thousand more words devoted to them. However, this essay is already long, so I leave these subjects to another person to cover in depth.

But there is one final thing I want to discuss. It is the very real possibility that lab robotics, cloud labs, and everything related to them, will not actually fundamentally alter the broader problems that drug discovery faces.

You may guess where this is going. It is time to read a Jack Scannell paper.

In Jack’s 2022 Nature Reviews article, ‘Predictive validity in drug discovery: what it is, why it matters and how to improve it’1, he and his co-authors make a simple argument: the thing that matters most in drug R&D is not how many candidates you can test, but how well your tools for evaluating those candidates correlate with what actually works in humans. They call this ‘predictive validity’, and they operationalize it as the correlation coefficient between the output of whatever decision tool you’re using—a cell-based assay, an animal model, a gut feeling—and clinical utility in actual patients. The primary takeaway here is their demonstration that a 0.1 absolute change in this correlation—shifting from, say, 0.5 to 0.6—can have a bigger impact on the positive predictive value of one’s R&D pipeline than screening ten times, or even a hundred times, more candidates.

They illustrate this with a fun historical example: in the 1930s, Gerhard Domagk screened a few hundred dyes against Streptococcus in live mice and discovered sulfonamide antibiotics. Seven decades later, GSK ran 67 high-throughput screening campaigns, each with up to 500,000 compounds, against isolated bacterial protein targets, and found precisely zero candidates worthy of clinical trials. How could this be? It is, of course, because the mice were a better decision tool than the screens, as they captured the in-vivo biology that actually mattered.

What is the usual use-case for lab robotics? It is meant to be a throughput multiplier. It lets you run more experiments, faster. And Scannell is stating that moving along the throughput axis—running 10x or 100x more experiments through the same assays—is surprisingly unimpressive compared to even modest improvements in the quality of those assays. And given the failure rate of drugs in our clinical trials, which hover as high as 97% in oncology, the assays are empirically not particularly good.

But, to be clear, this is not an anti-automation take. It is a reframing of what automation should be for.

It feels like the value that the lab-robotics-of-tomorrow will bring to us will almost certainly not be in gently taking over the reins of existing workflows and running them themselves. It will be in enabling different experiments, better ones, ones with higher predictive validity, at a scale that would be impossible without automation. And this doesn’t require any suspension of disbelief about what ‘autonomous science’ or something akin to it may one day bring! The arguments are fairly mundane.

In the same Scannell paper, he argues that companies should be pharmacologically calibrating their decision tools, as in, running panels of known drugs, with known clinical outcomes, through their assays to measure whether the assay can actually distinguish hits from misses. Almost nobody does this, because it is expensive, tedious, and produces neither a publication nor a patent. But if per-experiment costs drop far enough, if they no longer require expensive human hands to perform, calibration becomes economically rational, and the industry could move from assuming that a given assay is predictive to measuring whether it is. Similarly, given the 50% irreproducibility rate in preclinical research, it may be the case that many otherwise ‘normal’ assays are yielding useless results, entirely because they are performed manually, by individual researchers with slightly different techniques, in labs with slightly different conditions, who did not have the instruments needed to validate their reagents. Sufficiently good cloud automation could free these assays from their dependence on individual hands, and allow higher-standard experimentation to be reliably performed at scale.

In other words: if you follow the trend-lines, if per-experiment costs continue to fall, if the translation layers keep getting better, if the cloud labs keep centralizing and vertically integrating and driving prices down further still, then at some point, perhaps not far from now, it becomes rational to do the things that everyone already knows they should be doing but can't currently justify. And this alone, despite its relative banality, may be enough to alter how drug discovery as a discipline is practiced.

Slight correction on this excellent article - Ginkgo RACs aren’t that recent of a push- the tech (and Will Serber) was acquired from Zymergen and the scheduling software was under development for years there. The intelligence layer integration (LLMs) is recent though.

It may seem like a long shot now but the way I see lab automation driving value is by screening at a scale that allows models to understand bio better. Data generated at scale from automated experiments can be used to build better models that function as 'predictive assays' themselves, allowing us to make better in-silico predictions about which drugs will actually work in practice. If both generative drug design/discovery and lab automation succeed, then maybe one day we’ll have precision medicine tailored to individual patients at scale.