The ML drug discovery startup trying really, really hard to not cheat (Leash Bio)

6k words, 27 minutes reading time

Note: I’ll be Austin until Jan 3rd, and in San Francisco (for JPM) from Jan 3rd-17th, message me on X/email to hang out! Also, thank you to Ian Quigley and Andrew Blevins, the two co-founders of Leash Bio, for answering the many questions that arose while writing this essay.

Introduction

What I will describe below is a rough first approximation of what it is like to work in the field of machine-learning-assisted small-molecule design.

Imagine that you are tasked with solving the following machine-learning problem:

There are 116 billion balls of varying colors, textures, shapes, and sizes in front of you. Your job is to predict which balls will stick to a velcro strip. To help start you off, you’re given a training set of 10 million balls that have already been tested; which ones stuck and which ones didn’t. Your job is to predict the rest. You give it your best shot, train a very large transformer on 80% of the (X, Y) labels, and discover that you’ve achieved an AUC of .76 on a held out 20% set of validation balls. Not too shabby, especially given that you only had access to .008% of the total space of all balls. But, since you’re a good hypothetical scientist, you look more into what balls you did well on, and which balls you did not do well on. You do not immediately find any surprises; there is mostly uniform error across color, textures, shapes, and sizes, which are all the axes of variation you’d expect exists in the dataset. But perhaps you’re a really good hypothetical scientist, and you decide that to be certain of the accuracy here, you’ll need to fly in the top ball-velcro researcher in the world to get their take on it. You do so. They arrive, take one look at your results, and burst out in laughter.‘ What’, you stutter, ‘what’s so funny?’. In between tears and convulsions, the researcher manages to blurt out, ‘You fool! You absolute idiot! Nearly all the balls in both your training set and test set were manufactured between 1987 and 2004, using a process that was phased out after the Guangzhou Polymer Standardization Accords of 2005! Your ball-velcro model is not a ball-velcro model at all, but rather a highly sophisticated detector of Guangzhou Polymer Standardization Accords compliance!’ The researcher collapses into a chair, still wheezing.

Actually, this hypothetical situation is easier than the real one, since there are several orders of magnitude more small-molecules in existence than the 116 billion balls, and there are also a few tens-of-thousands of possible velcro strips— binding proteins—in existence too, each with their own unique preferences.

Given the situation here, there is a fair bit of cheating that goes on in this field. Most of it is accidental and maybe even unavoidable, and truthfully, it is difficult to not feel at least some sympathy for the researchers here. There is something almost cosmically unfair about trying to solve a problem where the axes of variation you don’t know about vastly outnumber the axes you do, making it so the space of possible ways you could be wrong is practically infinite. Can we fault these people for pretending that their equivalence to the compliance-detection-machine is actually useful for something?

Well, yes, but we should also understand that the incentives aren’t exactly set up for being careful, thinking really hard, and trying to ensure that the model did the Correct Thing. This is true even in the private sector, where the timelines for end utility of these models are far off in the horizon, where the feedback loops are so long that by the time anyone discovers your model was secretly a Guangzhou Accords detector, there are no meaningful consequences for anybody involved.

This is why I think it is important to shine a spotlight on people trying to, despite the situation, do the right thing.

And this essay is my attempt to highlight one such party: Leash Bio.

Leash Bio is a Utah-based, 12~ 9-person startup founded in 2021 by two ex-Recursion Pharmaceutical folks: Ian Quigley and Andrew Blevins. My usual biotech startup essays are about places that have strange or especially out-there scientific theses, so I spend a long time focusing on the details of their work, where it may pay off big, and the biggest risks ahead.

I will not do this here, because Leash Bio actually has both a very well-trodden scientific thesis (build big datasets of small-molecules x protein interactions and train a model on it) and a very well-trodden economic thesis (use the trained model to design a drug). There’s clearly some value here, at least to the extent that any ML-for-small-molecule-development play has value. There’s also some external validation: a recent partnership with Monte Rosa Therapeutics to develop binders to novel targets.

Really, what is most unique about Leash is almost entirely that, despite how hard it is to do so, they have a nearly pathological desire to make sure their models are learning the correct thing. They have produced a lot of interesting artifacts from this line of research, much of which I think should have more eyes on. This essay will dig deep into a few of them. If you’re curious to read more about their research, they also have their own fascinating blog here.

Some of Leash’s research

The BELKA result

You may recall an interesting bit of drama that occurred just about a year back between Pat Walters—who is one of the chief evangelists of ‘many people in the small-molecule ML field are accidentally cheating’ sentiment—and the authors of DiffDock, which is a (very famous!) ML-based, small-molecule docking model.

The drama originally kicked off with the publication of Pat’s paper ‘Deep-Learning Based Docking Methods: Fair Comparisons to Conventional Docking Workflows’, which claimed to find serious flaws with the train/test splits of DiffDock. Gabriel Corso, one of the authors on the DiffDock paper, responded to the paper here, basically saying ‘yeah, we already knew this, which is why we released a follow-up paper that directly addressed these’. After many comments back and forth, the saga mostly ended with the original Pat paper having this paragraph being appended to it:

The analyses reported here were based on the original DiffDock report [1], with performance data provided directly by authors of that report, corresponding exactly to the published figures and tables. Subsequently, in February 2024, a new benchmark (DockGen) and a new DiffDock version (DiffDock-L) was released by the DiffDock group [21]. This work post-dated our analyses, and we were unaware of this work at the time of our initial report, whose release was delayed following completion of the analyses.

All’s well that ends well, I suppose.

But what was the big deal with the train/test splits anyway?

To keep it simple: the original DiffDock paper trained on pre-2019 protein-ligand complexes, and tests on post-2019 protein-ligand complexes. This may not be too terrible, but you can imagine one failure mode of this is that there is a lot of conservation in the chemical composition of binding domains, making it so the model is more interested in memorizing binding-pocket-y residues rather than trying to learn the actual physics of docking. So, when presented with a brand new binding pocket, it’d fail. And indeed, this is the case.

In the follow-up DiffDock-L paper, the authors moved to a benchmark that ensured that proteins with the same protein binding domains were either only in the train or only in the test dataset. Performance fell, but the resulting model was able to demonstrate much better diversity to a broader range of proteins.

Excellent! Science at work. But there is an unaddressed elephant in the room: what about chemical diversity? DiffDock-L may very well generalize to unseen protein binding pockets, but can it do well on ligands that are very structurally different from ligands it was trained on? This isn’t really a gotcha for DiffDock, because it turns out that the answer is ‘surprisingly, yes’. From a paper that studied the topic:

Diffusion-based methods displayed mixed behavior. SurfDock showed declining performance with decreasing ligand similarity on Astex, but surprisingly improved on PoseBusters and DockGen, suggesting resilience to ligand novelty in more complex scenarios. Other diffusion-based and all regression-based DL methods exhibited decreasing performance on Astex and PoseBusters, but remained stable—or even improved slightly—on DockGen, likely implying that unfamiliar pockets, rather than ligands, pose the greater generalization barrier.

But docking is not the big problem, not really.

The holy grail for protein-ligand-complex prediction is predicting affinity; not only where a small-molecule binds to, but how tightly. And here, it turns out that it is incredibly easy to mislead oneself on how well models can do here. In an October 2025 Nature Machine Intelligence paper titled ‘Resolving data bias improves generalization in binding affinity prediction’, they say this:

This large gap between benchmark and real-world performance [of binding affinity models] has been attributed to the underlying training and evaluation procedures used for the design of these scoring functions. Typically, these models are trained on the PDBbind database37,38, and their generalization is assessed using the comparative assessment of scoring function (CASF) benchmark datasets10. However, several studies have reported a high degree of similarity between PDBbind and the CASF benchmarks. Owing to this similarity, the performance on CASF overestimates the generalization capability of models trained on PDBbind10,39,40. Alarmingly, some of these models even perform comparably well on the CASF datasets after omitting all protein or ligand information from their input data. This suggests that the reported impressive performance of these models on the CASF benchmarks is not based on an understanding of protein–ligand interactions. Instead, memorization and exploitation of structural similarities between training and test complexes appear to be the main factors driving the observed benchmark performance of these models35,36,41,42,43.

What a pickle!

Now, the paper goes on to come up with its own split from the PDB that takes into account a combination of protein similarity, binding conformation similarity, and, most relevant to us, ligand similarity. How do they judge ligand similarity? A metric called the ‘Tanimoto score’, which seems like a pretty decent way to get to better generalization per another Pat Walters essay.

Well, that’s that, right? Have we solved the ball problem before?

Not quite. Tanimoto-based filtering is an improvement, but it is still an exercise in carving up existing public data more carefully. Why is that a problem? Because public data are not random samples from chemical space, but are rather the the accumulated residue of decades of drug discovery programs and academic curiosity. Because of that, even if you filter out molecules with Tanimoto similarity above some threshold, you might still be left with test molecules that are “similar” in ways that Tanimoto doesn’t capture: similar pharmacophores, similar binding modes, similar target classes. A model might still be learning something undesirable, like, “this looks like a kinase inhibitor I’ve seen before”, and there is really no way to stop that no matter how you split up the public data.

How worried should we be about this? Surely at a certain level of scale, the Bitter Lesson takes over and our model is learning something real, right?

Maybe! But we should test that out, right?

Finally with this background context, we can return to the subject of this essay.

In late 2024, Leash Bio, in one of the most insane public demonstrations I have yet seen from a biotech company, issued a Kaggle challenge to all-comers: here’s 133 million small molecules generated via a DNA-encoded library (which we’ll discuss more about later) that we’ve screened against three protein targets, and here’s binary binding labels for all of them. The problem statement is as follows: given this dataset—also known as ‘BELKA’, or Big Encoded Library for Chemical Assessment—predict which ones bind.

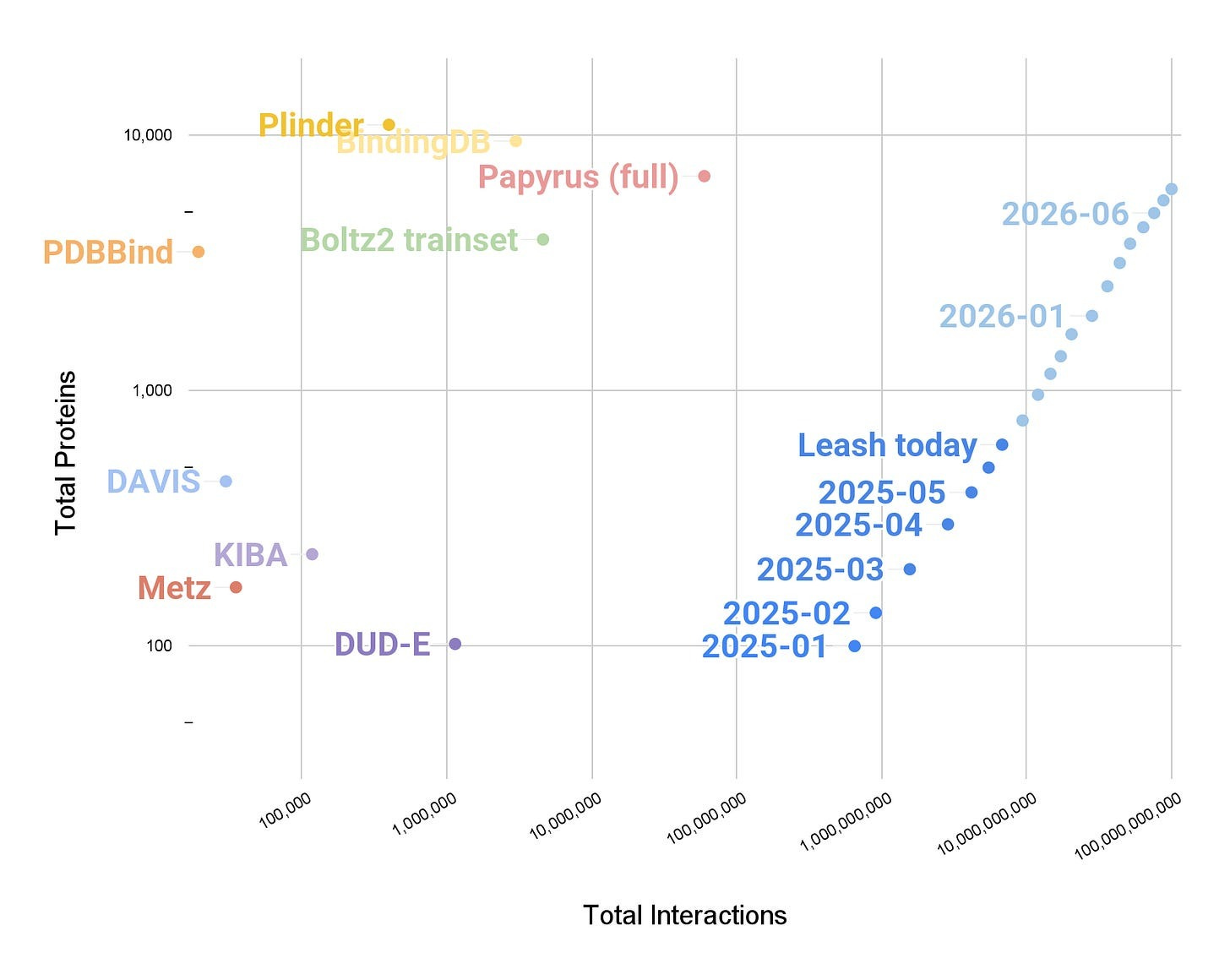

How large is this dataset in relative terms? In the introductory post for the dataset, Leash stated this:

The biggest public database of chemistry in biological systems is PubChem. PubChem has about 300M measurements (11), from patents and many journals and contributions from nearly 1000 organizations, but these include RNAi, cell-based assays, that sort of thing. Even so, BELKA is >10x bigger than PubChem. A better comparator is bindingdb (12), which has 2.8M direct small molecule-protein binding or activity assays. BELKA is >1000x bigger than bindingdb. BELKA is about 4% of the screens we’ve run here so far.

As for the data splits, Leash provided three:

A random molecule split. The easiest setting.

A split where a central core (a triazine) is preserved but there are no shared building blocks between train and test.

A split based on the library itself. In other words, it was a test set with entirely different building blocks, different cores, and different attachment chemistries, molecules that share literally nothing with the training set except that they are, in fact, molecules. The hardest setting.

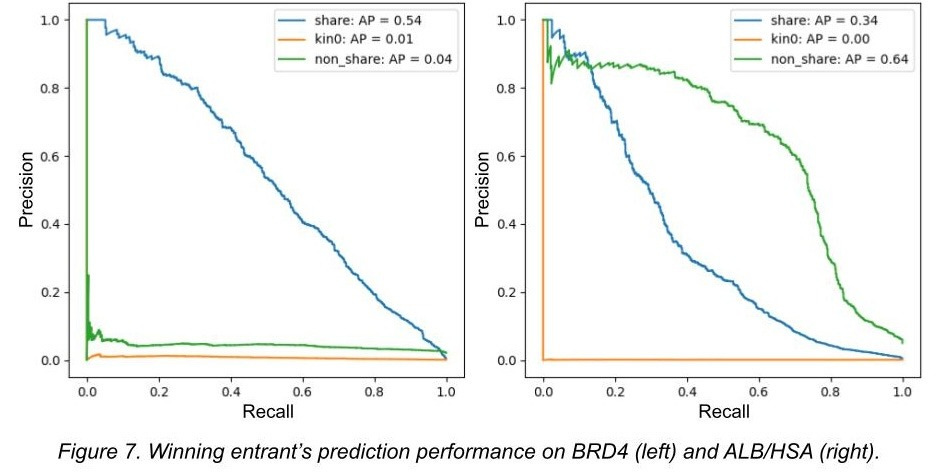

Here is the hilarious winning result from the Kaggle competition, where ‘kin0’ refers to the 3rd data split:

In other words, a model was trained on a dataset that is an order of magnitude larger than any dataset that has come before it. And it completely failed to generalize in any meaningful capacity, being nearly perfectly equivalent to random chance. In turn, Leash’s blog post covering the whole matter was titled ‘BELKA results suggest computers can memorize, but not create, drugs’.

Now, it is worth protesting at this result. Chemistry is complex, yes, but it is almost certainly bounded in its complexity. So, one defense here is that diversity matters more than scale, and that, say, bindingdb’s ~2.8 million data-points, despite being far smaller, span far more of chemical space than BELKA’s 133 million. Moreover, bindingdb contains hundreds of targets, whereas BELKA only contains 3. In comparison, BELKA is, chemically speaking, incredibly small. Is it any wonder models trained on it, and it alone—as these were the rules for its Kaggle competition—don’t generalize well?

These are all fair arguments. Is this entire thing based on a contrived dataset?

There is an easy way to assuage our concerns. We can just load up a state-of-the-art binding affinity model, one that has been trained on vast swathes of publicly available data out there, and try it out on a BELKA-esque dataset. Say, Boltz2. How does that model perform?

The Hermes result

Well, BELKA can’t just be used out of the box. To ensure that they are truly testing ligand generalization, Leash first curated a subset of their data that has no molecules, scaffolds, or even chemical motifs in common with training sets used in Boltz2 training. This shouldn’t be any trouble for a model that has sufficiently generalized!

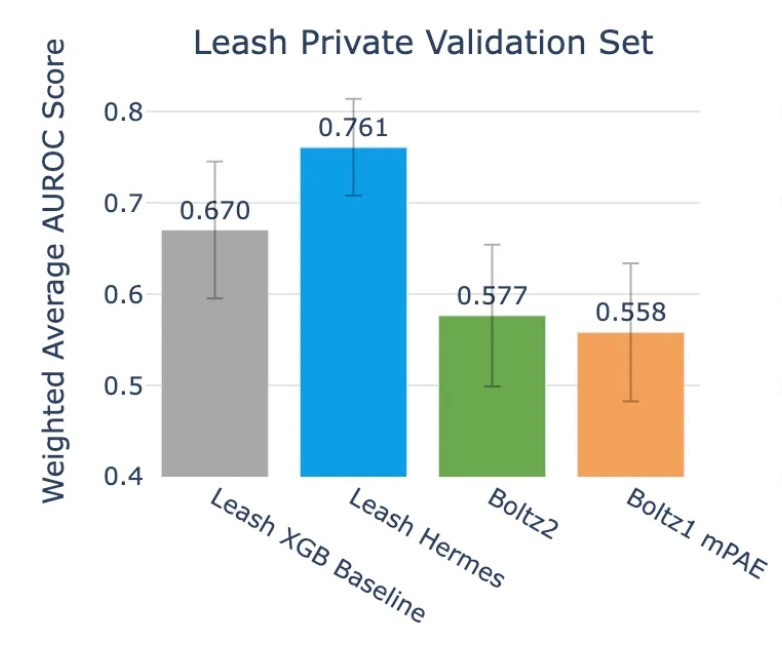

At the same time, they put Boltz2 in a head-to-head comparison against a lightweight sequence-only, 50M parameter (!!!) transformer called Hermes trained by the Leash team. Given 71 proteins, 7,515 small molecule binders, and 7,515 negatives, the task was to predict the likelihood of binding given a pair of proteins and small-molecules.

But before we talk about the results, let’s quickly discuss Hermes. Specifically, that Hermes was not trained on any public data, but rather, on the combined sum of all the binding affinity data that Leash has produced. How much of this data is there? At the time Hermes was trained, just shy of 10B ligand-protein interactions. At the time this essay you are reading was published, it is now 50B interactions. Both of these numbers are several orders of magnitude higher than any other ligand x protein dataset in existence.

Finally, we can move onto the results.

Hermes did decently, grabbing an average AUROC of .761. Notably, the validation set here is meant to have zero chemical overlap with Hermes train set, which is something we’ll talk about more in the next section, which makes the result even more striking.

On the other hand, Boltz2 scores .577.

Hmm. Okay.

You could imagine that one pointed critique of this whole setup is that the validation dataset is private. Who knows what nefarious things Leash could be doing behind the scenes? Also, it may be the case that Leash is good in whatever space of chemistry they have curated, whereas Boltz2 is good in whatever space of chemistry exists in public databases. The binding affinity results in the Boltz2 paper are clearly far above chance, so this seems like a perfectly reasonable reconciliation of the results.

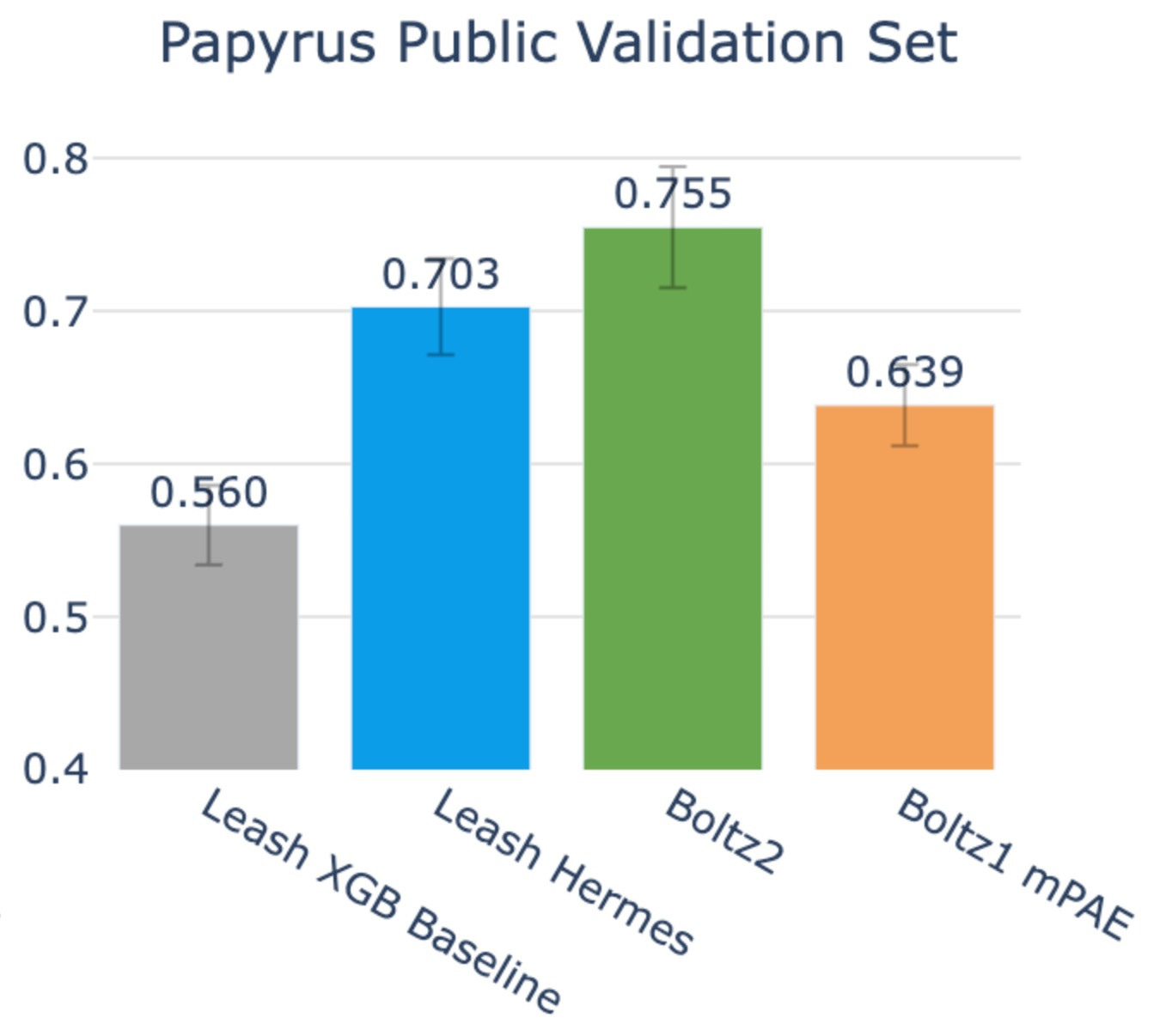

Well, Leash also curated a subset of data from Papyrus, a publicly available dataset of binding affinity data, and threw both Boltz2 and Hermes at that.

From their post:

Papyrus is a subset of ChEMBL and curated for ML purposes (link). We subsetted it further and binarized labels for binding prediction. In brief, we constructed a ~20k-sample validation set by selecting up to 125 binders per protein plus an even number of negatives for the ~100 human targets with the most binders, binarizing by mean pChEMBL (>7 as binders, <5 as non-binders), and excluding ambiguous cases to ensure high-confidence, balanced labels and protein diversity. Our subset of Papyrus, which we call the Papyrus Public Validation Set, is available here for others to use as a benchmark. It’s composed of 95 proteins, 11675 binders, and 8992 negatives.

On this benchmark, Boltz2 accuracy rose up to .755, and Hermes stayed in roughly the same territory it was previously at: .703, its confidence interval slightly overlapping with that of Boltz2’s.

So, yes, Boltz2 does edge out here, but given that the chemical space of Papyrus substantially overlaps with the CheMBL-derived binding data trained on by Boltz2, you may naturally expect this.

So, to summarize where we are at: Leash’s in-house model, trained exclusively on their proprietary data, performs about as well on public benchmarks as a model that was partially trained on those benchmarks.

And on Leash’s private data, which, crucially, has little overlap with public training sets as measured by Tanimoto scores (also included in their post), their model handily beats the state of the art.

This is all very exciting! But I want to be careful here and explicitly say that the the story here is far from complete. What we can say, with confidence, is that Leash has demonstrated something important: a lightweight model trained on dense, high-quality, internally consistent data can compete with architecturally sophisticated models trained on the sprawling, noisy, heterogeneous corpus of public structure databases. This is made even more interesting by the fact that Hermes is not structure based, allowing it to be 500x~ faster than Boltz2, the advantages of which are discussed in this other Leash post.

But what is not yet clear is proof that Leash has cracked the generalization problem. I think they are asking the right questions, and perhaps have early results that the yielded answers are interesting, but chemical space is large, far larger than anybody could ever imagine, and it would be naive of anyone to claim that the two simple benchmarks here are sufficient to declare anything for either side.

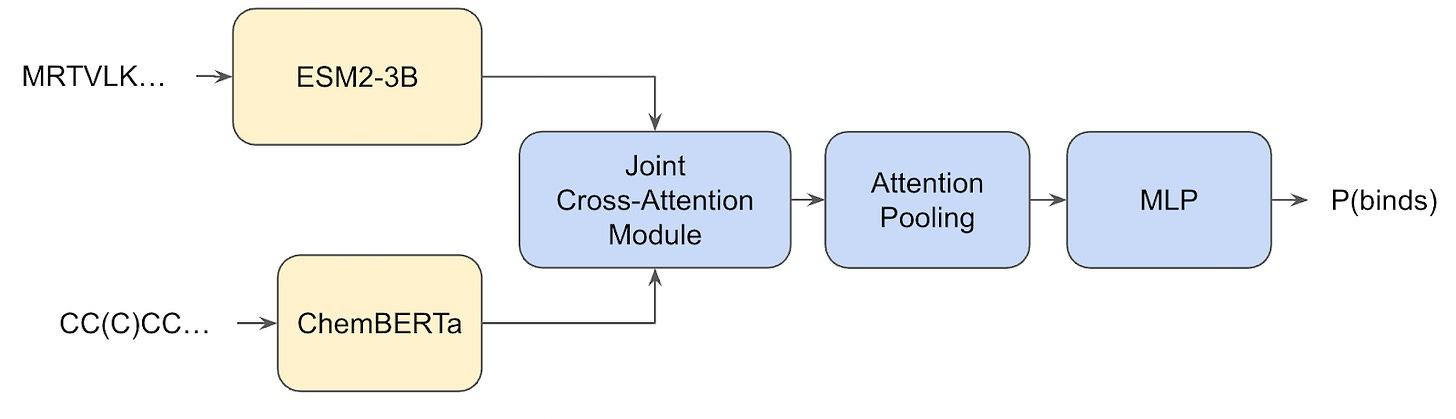

But even after tempering my enthusiasm, I still find the results fascinating. The only outstanding question is: where does this seemingly high generalization performance actually come from? Is it from the extremely large dataset? Surely partially, but, again, chemical space is so extraordinarily vast that a few tens-of-millions of (sequence-only!) samples from it surely is a drop in the bucket, and . Is it perhaps from the Hermes architecture? Also unlikely, because remember, the model itself is dead-simple, just a simple transformer that uses the embeddings of two pre-trained models (ESM2-3B and ChemBERTa).

What’s going on? Where is generalization arriving from? Well, we’ll get back to that, because first I want to talk about how the Leash curated their own train/test splits.

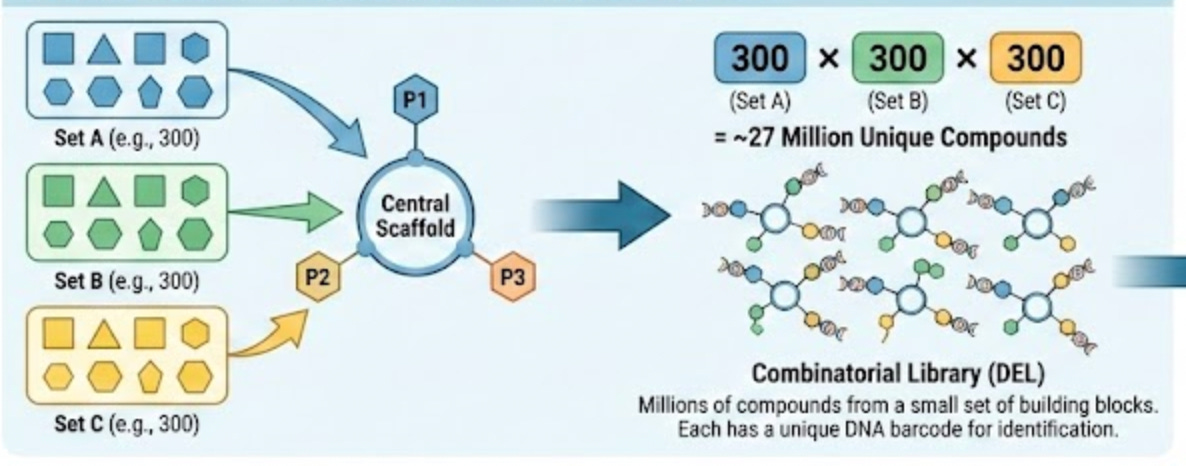

The train/test split result

As I’ve been repeating throughout this essay, Leash’s model is trained using DNA-encoded chemical libraries. These are combinatorial libraries where each small molecule is tagged with a unique DNA barcode that identifies its structure. The molecules themselves are built up from discrete building blocks. You have a central scaffold, and then you attach different pieces at different positions. A typical DEL molecule might have three attachment points, each of which can hold one of hundreds of different building blocks. Multiply those possibilities together and you can get millions of unique compounds from a relatively small set of starting materials.

It feels wrong to give this explanation without an associated graphic, so I asked Gemini to create one:

This is great for generating diverse molecules, but also for splitting a chemical dataset, because it allows you to split them by the building blocks they share. If there are, say, 3 possible building blocks in the library, that means a rigorous way to split things is to ensure that there are no building blocks in the train set that are in the test set.

But you may immediately see a problem here; what if two different building blocks have very chemically similar properties? This can be easily remedied by not only ensuring that there are no building-block overlaps, but also checking that the chemical fingerprint of building blocks in the train set are sufficiently dissimilar from those in the test set. In other words, you cluster the building blocks by chemical similarity, and then filter any that are in the train set from the test set.

And they did exactly this. From their post:

Our Leash private validation set is this last category: it’s made of molecules that share no building blocks with any molecules in our training set, and also the training set doesn’t have any molecules containing building blocks that cluster with validation set building blocks. It’s rigorous and devastating: splitting our data this way means our training corpus is roughly ⅓ of what would be if we didn’t do a split at all (0.7 of bb1*0.7 of bb2*0.7 of bb3 = 0.343)…

In exchange for losing all that training data, we now have a nice validation set where we can be more confident that our models aren’t memorizing, and we can use it to make an honest comparison to other models that have been trained on public data.

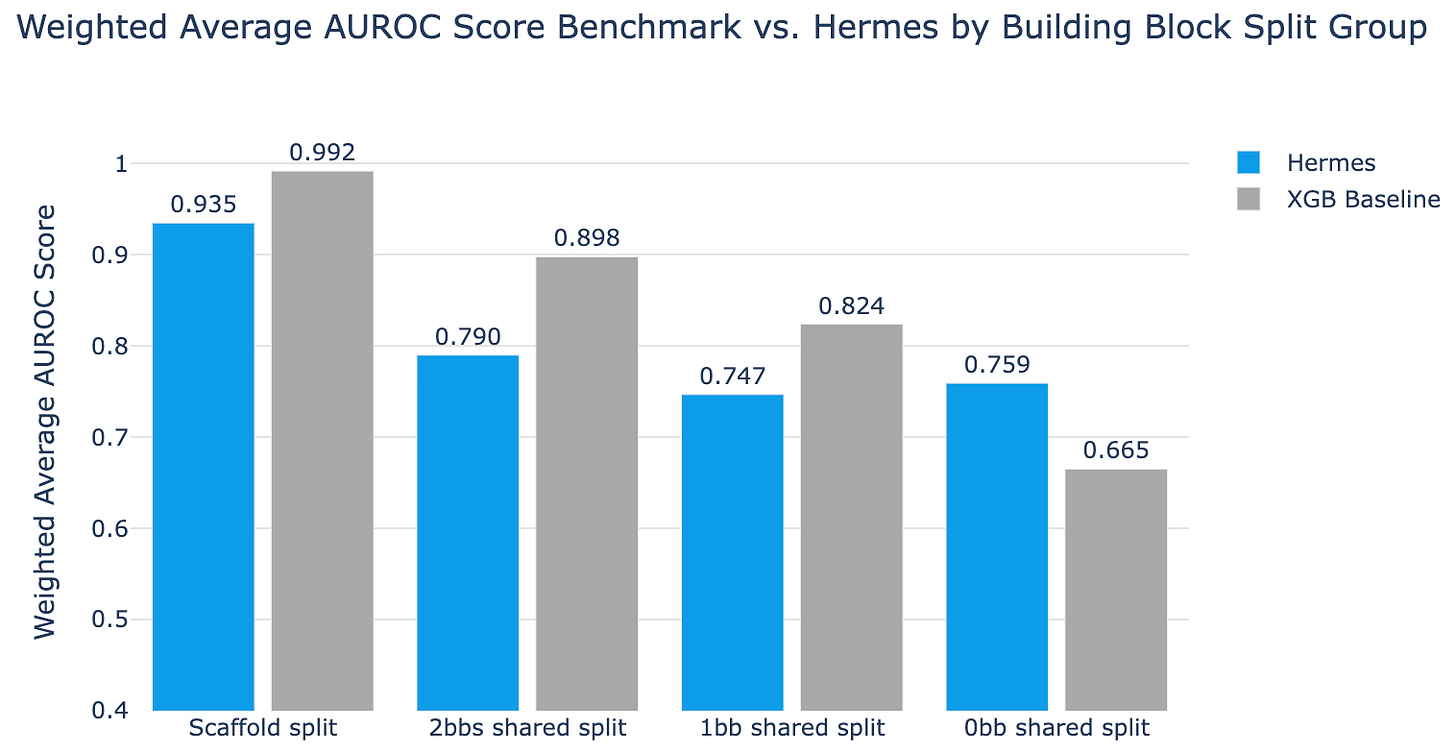

Using this dataset, they applied Hermes (and XGBoost as a baseline) to four increasingly difficult splits of the data: a naive split based on chemical scaffold, 2 building blocks shared split, 1 building block shared split, and 0 building blocks shared + no chemical fingerprint clusters shared. The results are as follows:

Here, simple XGBoost beats Hermes on almost every split other than the hardest one. Only when you ensure that there are zero shared building block clusters, when you truly force the model to chemically novel territory, does the more complex Hermes pull ahead.

Okay, this is a fine result, and it does rhyme with the theme of the essay w.r.t ‘being rigorous’, but this should raise more questions than it answers. As a result of how they have constructed the training dataset for Hermes, wouldn’t we expect it to have a relatively small area of ‘chemical space’ to explore? By going through this building-block and cluster filtering, surely the training data is almost comically O.O.D from the test set! And yet, as we mentioned in the last section, Hermes seems to display at least some heightened degree of chemical generalizability compared to state-of-the-art models! How is this possible?

It may have to do with the nature of the data itself: DNA-encoded libraries. Leash writes in their blog post that the particular type of data is perhaps uniquely suited for forcing a model to actually learn some physical notion of what it means to bind to something:

Our intuition is that by showing the model repeated examples of very similar molecules - molecules that may differ only by a single building block - it can start to figure out what parts of those molecules drive binding. So our training sets are intentionally stacked with many examples of very similar molecules but with some of them binding and some of them not binding.

These are examples of “Structure-activity relationships”, or SAR, in small molecules. A common chemist trope that illustrates this phenomena is the “magic methyl” (link), which is a tiny chemical group (-CH3). Magic methyls are often reported to make profound changes to a drug candidate’s behavior when added; it’s easy to imagine that new greasy group poking out in a way that precludes a drug candidate from binding to a pocket. Remove the methyl, the candidate binds well.

DELs are full of repeated examples of this: they have many molecules with repeated motifs and small changes, and sometimes those changes affect binding and sometimes they don’t.

Neat! This all said, the usage of DELs is at least a little controversial, due to it often producing false negatives, being limited in overall chemical space, and the actual hits from DEL’s not being particularly high-affinity. Given that I do not actively work in this area, it is difficult for me to give a deeply informed take here. But it is worth mentioning that even if the assay seems to have its faults, the fact that Hermes performs competitively on Papyrus—a public benchmark derived from ChEMBL that has nothing to do with DEL chemistry—suggests that whatever Leash’s models are learning cannot purely be an artifact of the DEL format. Of course, it is almost certainly the case that Hermes has its own failure modes and time will tell what those are.

And with this, we can arrive to the present day, with a very recent finding from Leash over something completely unrelated to Hermes.

The ‘Clever Hans’ result

Truthfully, I’ve wanted to cover Leash for a year now, ever since the BELKA result. But what finally got me to sit down and do it was an email I received from Ian Quigley, a co-founder of Leash, recently on November 27th, 2025. In this email, Ian attached a preprint he was working on, written alongside Leash’s cofounder Andrew Blevins, that described a phenomenon that he dubbed, ‘Clever Hans in Chemistry’. The result contained in the article was such a perfect encapsulation of the cultural ethos I—and many others—have come to associate with Leash, that I finally wrote the piece I’d been putting off.

So, what is the ‘Clever Hans’ result? Simple: it is the observation that molecules created by humans will necessarily carry with it the sensibilities, preferences, and quirks of the human who made them.

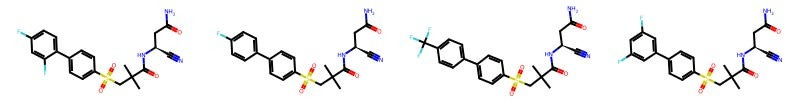

For example, here are some molecules created by Tim Harrison, a distinguished medicinal chemist at Queen’s University Belfast.

And here are some other molecules made by Carrie Haskell-Luevano, who is a chemical neuroscientist professor at the University of Minnesota’s College of Pharmacy.

I don’t know any medicinal chemistry! You may not either! And yet, you can see that there is an eerie degree of same-ness within each chemist’s portfolio. And if we can see it, can a model?

Yes.

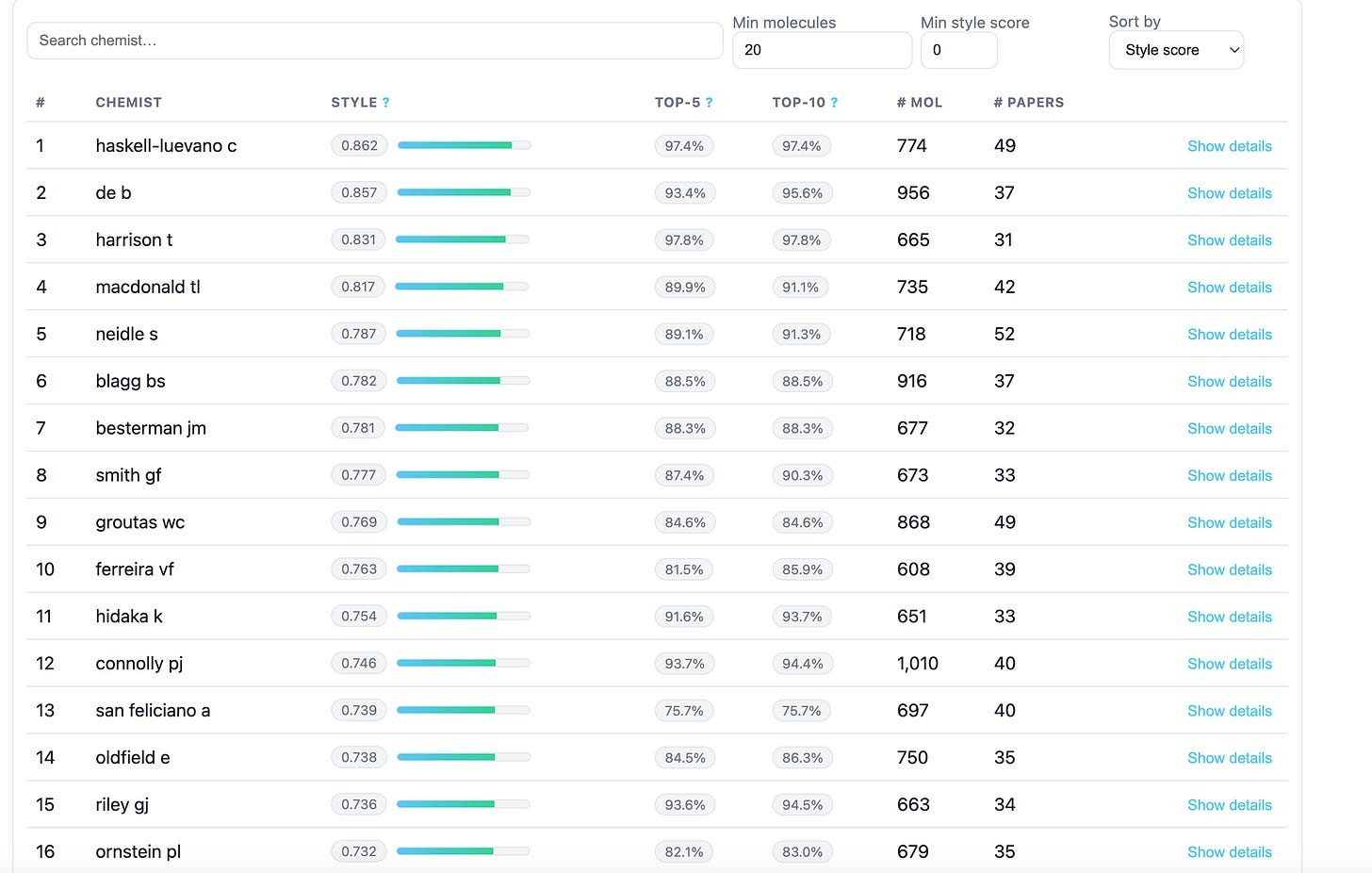

Using ChEMBL, Leash collated together a list of chemists who they considered prolific (>30 publications, >600 molecules contributed), scrapped all their molecules, and then trained a very simple model to play Name That Chemist.

Out of 1815 chemists, their trained model had a top-1 accuracy of 27%, and a top-5 accuracy of 60% in being able to name who created an arbitrary input molecule.

If curious, Leash also set up a leaderboard for you to see how distinctive your favorite chemist is! And while some chemists’ molecules are far harder to suss out than others, the vast majority of them did leave a perceptible residue on their creations.

This may seem like a fun weekend project, but the implications start to get a little worrying when you realize that the extreme similarity amongst a chemists molecules are less of an idiosyncratic behavior, and more of a career-long optimization process of creating molecules that do X, and molecules that do X may very well end up looking a particular way. Which means that if a model can detect the author, it can infer the intent. And if it can infer the intent, it can predict the target. And if it can predict the target, it can predict binding activity. All without ever learning a single thing about why molecules actually bind to proteins.

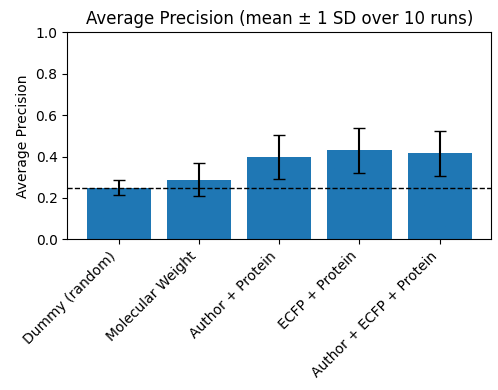

Is this actually true though? It seems so. Using a split based on chemical scaffold (which is a pretty common, though increasingly discouraged practice), Leash found that that there is no functional difference in accuracy between giving a model a rich molecular description of the small-molecule (ECFP), and only giving a model the name of the author who made it. Even worse, both seem to encode roughly the same information.

They have a few paragraphs from their preprint that I really want to repeat here:

Put differently, much of the information that a simple structure-based model exploits in this setting is explainable by chemist style. The activity model does not need to infer detailed chemistry to perform well; it can instead learn the sociology of the dataset—how different labs behave, which series they pursue, and which targets they favor.

….

We interpret this as evidence that public medicinal-chemistry datasets occupy a narrow “chemist- style” manifold: once a model has learned to recognize which authors a molecule most resembles, much of its circular-fingerprint representation is already determined. This reinforces our conclusion that apparent structure–activity signal on CHEMBL-derived benchmarks is tightly entangled with chemist style and data provenance.

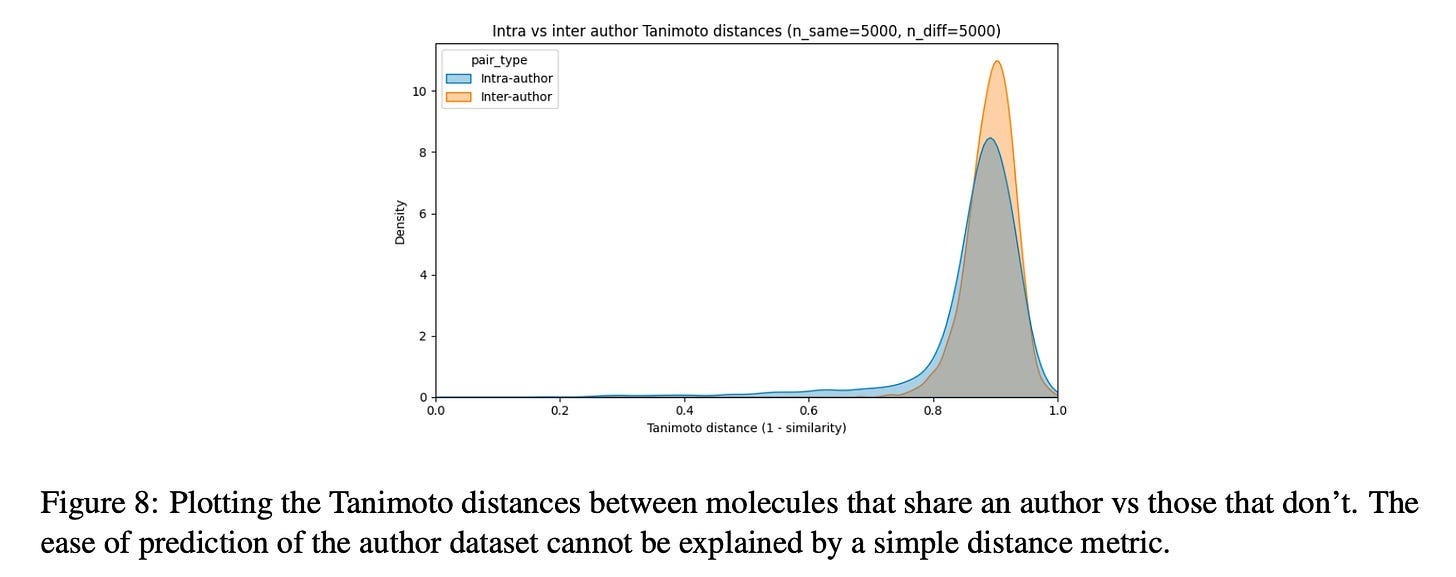

Now wait a minute, you may cry, this is just repeating the same point made in the last section about rigorous train/test splitting! And yes, this result does certainly rhyme with that. But the difference here is that the author signal seems to be inescapable through the standard deconfounding technique. Consider the following plot from the paper:

If chemist style were simply “chemists make similar-looking molecules,” you’d expect clear separation here—intra-author pairs clustering at low distances, inter-author pairs at high distances. But the distributions almost completely overlap. Both peak around 0.85-0.9 Tanimoto distance. The intra-author distribution has a slightly heavier left tail, but the effect is marginal. By the standard metric the field uses to assess molecular similarity, molecules from the same author are barely more similar to each other than molecules from different authors.

And yet, models can detect it. And it is almost certainly the case that binding affinity models trained on human-designed molecules are exploiting it.

But it gets worse. Authorship is just one axis of ‘human-induced chemical bias’ that we can easily study! There is a much more subtle one that Leash mentioned in a blog post over the subject: stage of development. Unfortunately, this type of data is a fair bit harder to get. They put it best in their blog post:

One dataset we wish we had includes how far along the medicinal chemistry journey a particular molecule might be. As researchers grow more confident in a chemical series, they’ll start putting more work into it, and this often includes more and more baroque modifications: harder synthesis steps, functional groups further down the Topliss tree, that kind of stuff.

Leash doesn’t need to worry about any of these issues for its own work, since their dataset is randomly synthesized in parallel by the millions, tested once, and either they bind or they don’t; the human intent that saturates public datasets simply isn’t present. So overall, this is a win for the ‘generate your own data’ side!

Either way, I still hope they study more and more ‘bizarre confounders in the public data’ phenomena in the future. How many other things like this exist beyond authorship and stage of development? What about institutional biases? The specifics of which building blocks happened to be commercially available where? Subscribe to the Leash blog to find out!

Conclusion

One may read all this and say, well, this is all well and good for Leash, but does every drug discovery task require genuine generalization to novel chemistry? Existing chemical space probably isn’t too bad to explore in!

And yes, I agree, and I think the founders of Leash would also. If a team is developing a me-too drug in well-explored chemical territory, a model cheating may be, in fact, perfectly fine. Creating a Guangzhou Polymer Standardization Accords detector would actually be useful!

But there is an awful lot of chemical space that is entirely unexplored, and almost certainly useful. What’s an example? I discuss this a little bit in an old article I wrote about the challenges of synthesizability in ML drug discovery if curious; an easy proof point here are natural products, which can serve as excellent starting points for drug discovery endeavors, and are known to have systemic structural differences between them and classic, human-produced molecules. Because of these differences, I would bet that the vast majority of small-molecule models out there would be completely unable to grasp the binding behavior of this class of chemical space, which, to be clear, almost certainly includes the current version of Hermes.

So, to be clear, as fun as it would be to imagine Leash doing all this model and data exploration work of a deep spiritual commitment to epistemic hygiene, the actual reason is almost certainly more pragmatic.

I gave the Leash founders a chance to read this article to ensure I didn’t make any mistakes in interpreting their results (nothing significant was changed based on their comments), and he offered an interesting comment: ‘While this piece is about us chasing down these leaks, I do want to say that we believe our approach really is the only way to enable a world where zero-shot creation of hit-to-lead or even early lead-opt chemical material is possible, particularly against difficult targets, allosterics, proximity inducers, and so on. Overfit models are probably best for patent-busting, and the past few years suggest to us that’s a losing battle for international competition reasons.’.

In other words, if the future of medicine lies in novel targets, novel chemotypes, novel modalities, you need models that have learned something fundamental about what causes molecules to bind to other molecules. They cannot cheat, they cannot overfit, they must really, genuinely, within its millions of parameters, craft a low-dimensional model of human-relevant biochemistry. And given how much they empirically care about finding ‘these leaks’, as Ian puts it, it’s difficult to not be optimistic about Leash’s philosophy being the best positioned to come up with the right solution to do exactly this.

Never stop writing, this is too good!! I’m sending this to my mom next time she asks me what I do. I don’t think there’s a more human explanation about cheminformatics on the internet. Big W.

I’ve had a hunch for a while that biased validation of models is the only valid yardstick so I made this many moons ago, https://github.com/Manas02/analogue-split

It’s very interesting to get answers to questions like “how does the model perform if the test set is completely made of molecules similar to training set but with significantly different bioactivity” i.e. how well does the model interpolate on between-series hits or “How does the model perform on test set which has no activity cliffs” i.e. how well does the model interpolate on within-series hits.

The results are exactly as you’d hope. Model performance decreases from within to between series predictions. Patterson et.al. in ‘96 (I think) used “neighbourhood behaviour” to explain this type of phenomenon.

PS. XGBoost can’t stop winning and it’s hilarious :p

Is the problem of bind/non-bind more practically useful than of predicting binding affinity values? If I understand correctly, the public results from Leash are around the former, while Boltz and similar models are trained for the later. I wonder what will happen if we instead trained the AF3-style architectures for the binary prediction task - I expect they would also get better - but how much better? And is the binary framing more useful or the value prediction/ranking?