Scaling microbial metagenomic datasets (Basecamp Research)

3.9k words, 18 minutes reading time

I think this startup is interesting! This is not a sponsored post, not meant to be anyone’s opinion other than my own, and is not investment advice. Here is some more information about why I write about startups at all.

Introduction

“Space is big. You just won't believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it's a long way down the road to the chemist's, but that's just peanuts to space.”

― Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

I always think about this quote whenever I think about microbes — a general term used to refer to bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

The genetic space that microbes occupy, often referred to as metagenomics, is large. A handful of soil alone contains trillions of microbes. They permeate every corner of the Earth, from sea mud in the Mariana Trench to the lower stratosphere. Each one adapts to the environments they reside in, slowly modifying itself to best survive.

While many species have been residents of their native environment for eons, they do not stay static in response to environment changes. The fast growth rates of many microbes afford it the ability to pass through selective pressures extraordinarily quickly. Just a year after the Chernoybl meltdown disaster in 1986, radioactive-resistant fungi was discovered within 30 kilometers of the power plant. The vast number of microbes along with their associated mutation rate make it, without question, the single largest source of biodiversity on our planet.

And, according to one paper, 99.999% of all microbes have yet to be discovered.

Basecamp Research, a London-based startup, seeks to change that. Founded in 2019 by Glen Gowers and Oliver Vince, Basecamp aims to build the largest and most diverse metagenomics dataset on Earth.

During this essay, we’ll discuss why they are doing this, what progress they have made, and how they plan to profit off of it. This posts was heavily assisted by Philipp Lorenz, the CTO of Basecamp Research, who hopped on a call with me to help clarify some aspects of the company. Huge shout-out to Kevin Yang for connecting us!

The value add

Why is metagenomics important?

Well, much of modern science is based off the proteins originally discovered in microbes. The Cas9 protein used in CRISPR therapeutics is part of an ancient bacterial immune system, nanopore sequencing rely on transmembrane proteins (αHL, MspA) found in most microbes, and so on. Mining nature for [things] is a tried and tested formula for finding useful proteins.

It’s incredibly important for AI tools in biology as well. Protein folding models, such as Alphafold2, are reliant on MSA’s, or multiple sequence alignments, to predict structures from input sequences. The data used to create MSA’s come from terabyte-sized sequence databases, many of which are metagenomic in nature. Even Alphafold3, released just a month ago, is still MSA-based.

Okay, so, metagenomics is important. But there are already large, open-sourced metagenomic datasets available. Mgnify, one of the largest repositories of environmental sequencing data, contains over 2.4 billion unique sequences. The data also has a reasonably high degree of diversity, clustering the sequences at 90% sequence identity yields around 600 million sequences, complete with the metadata of the environment it was extracted from.

So what value is Basecamp Research actually offering?

Part of the pitch is that much of the (open-sourced) metagenomic space is perhaps high diversity from a sequence standpoint, but not necessarily from an environmental one. A quick stroll through Mgnify’s dataset page will, in a purely eye-balling and non-scientific manner, lends some credence to this. Mgnify collates metagenomic data from studies undertaken by third party researchers, and most of the samples here seem reasonably simple. Soil gathered from a forest, microbiomes of healthy/diseased organisms, and the like. To Mgnify’s effort, there are a few interesting ones! Like data collected from the deepest point of the Baltic Sea. But the vast majority are environments that are reasonably similar to one another.

And environmental diversity matters!

While the aforementioned Cas9 and transmembrane proteins are relatively ubiquitous across domains of life, there are rarer proteins that only exist in certain biomes. Such as the Taq protein, heavily used in polymerase chain reactions due to its ability to retain its shape in high temperatures, was originally discovered in underwater hydrothermal vents. Outside of this extreme environment, it is unlikely the protein would be found.

Basecamp Research is an attempt to scale up microbial data from the environmental diversity side. The founding of the company actually stems from work exploring microbial diversity of Europe’s largest ice cap (Vatnajökull, Iceland). The paper that resulted from this is fascinating to read; the founders of the company went through 11 days of hiking through Arctic-level conditions, relied entirely on solar power, and sequencing was performed on-site at the glacier (likely to avoid microbial death or contamination) via a Nanopore sequencer.

As of today, Basecamp performs partnerships with expeditions around the world — such as organized sports in remote oceanic regions or cross-Atlantic oceanic journeys made via hot air balloons — sponsoring trips in exchange for sampled microbes along their journey. They literally have a section of their website titled ‘For Explorers’ for partnerships. And, since plenty of environments lack people who consistently visit them, they also have a few full time ‘explorers’ on staff whose job is to conduct sequencing in remote locations!

What have they accomplished?

The product

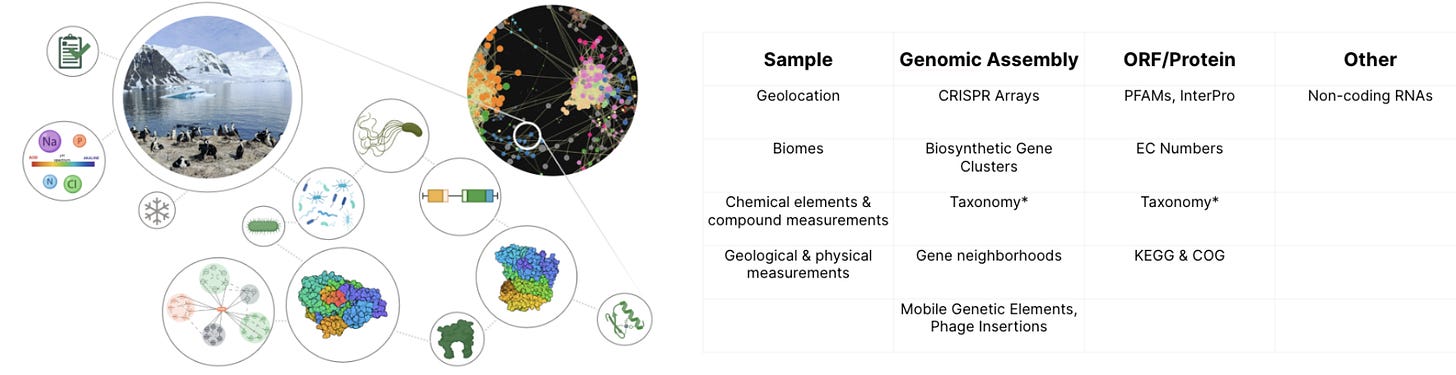

Their primary product is something called ‘BaseGraph’, which is a knowledge graph of all the data they have ever collected. According to an article from December 2023:

…BaseGraph, the largest knowledge graph of natural biodiversity, containing over 5.5B relationships with a genomic context exceeding 70 kilobases per protein. Their extensive long-read sequencing is complemented by comprehensive metadata collection, enabling them to link proteins of interest to specific reactions and desired process conditions.

It’s difficult to gauge how impressive this is compared to the open-source alternatives. Luckily, my conversation with Philipp shed some light on this!

In his eyes, BaseGraph is superior to open-source metagenomic datasets for one large reason that I rarely see mentioned in other news articles: they have put a lot of work into improving the data collection process itself. The environmental diversity is simply a way to exploit that improvement! In Basecamp’s eyes, traditional environmental samplings methods — which the open source metagenomics datasets primarily use — lack sufficient sequencing depth, cells aren’t lysed equally to expose genomic elements, and genomic assembly is often insufficient to find the really interesting stuff. This, amongst a long tail of other things, is part of Basecamps value add. I wasn’t provided many specifics here because their exact sequencing methodology is very much part of their core IP!

It’s an interesting angle for where the scientific ‘alpha’ of a metagenomics company can lie. And there is precedent to back up the difficulty of doing this. I’ve written before about the difficulties of sequencing microbiomes, which isn’t too far away from the difficulty of sequencing environmental microbes. If Basecamp is claiming a significant improvement here, it’s worth paying attention to.

Let’s switch to going over some Basecamp-published papers.

Papers

HiFi-NN annotates the microbial dark matter with Enzyme Commission numbers

Paper here. Published at NeurIPS MLSB December 2023.

Even though we can en-masse sequence the genomes of microbes, tying the resulting protein-coding regions of the genome to functional characteristics (e.g. transmembrane proteins, etc.) is still quite challenging. Around 30% of the microbial sequence space is fully unannotated, often described as ‘microbial dark matter’.

A functional characteristic that many people are often interested in are whether a protein is an enzyme — Taq and Cas9 are also enzymes — since enzymes have the ability to massively accelerate chemical reactions in precise, controllable ways. This is useful for a huge number of industrial applications.

Discovering these enzymes from these mass-collected datasets — i.e. mapping sequence to functional enzyme type — is the subject of this paper.

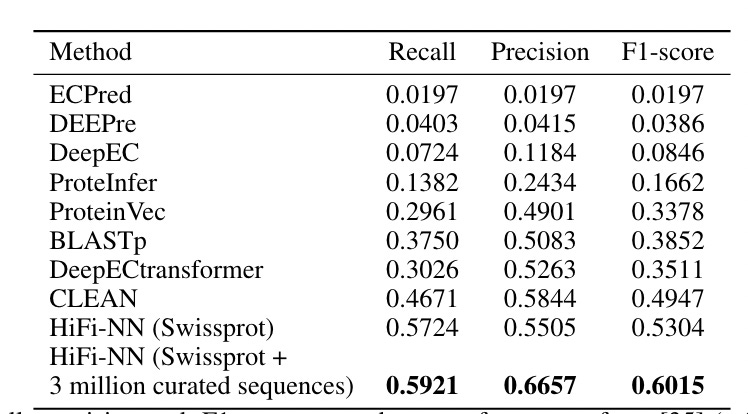

What did they do? The methodology in the paper is two-step: fine-tune ESM2 with a contrastive loss (trained on Swissprot data), and then, given an embedding of an input sequence, use K-nearest-neighbors of other embedded enzymes to find input enzyme category (or classify it as ‘not an enzmyme).

The nearest neighbor’s step is where Basecamp threw in their metagenomic dataset, vastly expanding the total number and diversity of reference enzymes.

One comment: It is clear how to do KNN with a labeled enzyme dataset (in their case, Swissprot), but less so with their own (presumably unlabeled?) metagenomic datasets. So…I’m assuming it is labeled. They say they are using "3 million curated sequences from our in-house database” and “We add sequences to include representation across [enzyme categories] for which Swissprot has few examples”, but it is unclear exactly what the curation process looks like, or how annotations for their in-house sequences were obtained.

In any case, it does seem like their method leads to an improvement in annotation accuracy by a fair margin compared to Swissprot alone, but still, the above points are important details! Would be curious to know how well Mgnify alone performed on this as well.

Improving AlphaFold2 performance with a global metagenomic & biological data supply chain

Paper here. Published on bioRxiv in March 2024.

This one is pretty simple: protein structures are important parts of the therapeutic design process. Knowing what parts of a protein are disordered, structured, bind-able, and so on, can vastly improve our ability to identify + exploit certain protein targets.

Of course, the current state of protein structure prediction, impressive as it is, is still largely insufficient to dramatically alter our current workflows. Still though, better structure prediction is always welcome!

As mentioned previously, MSA’s are often used as input to these models. As such, improving the underlying sequence data that the MSA is drawn from can be a way to eke out a performance bump with an existing protein structure model. And this is exactly what this paper tested.

What did they do? They ran structure predictions using a base Alphafold2 model, with MSA construction relying on the BaseGraph dataset and the usual MSA dataset. The method leads to a very mild aggregate bump across all structure prediction benchmarks (selected proteins from CASP15 and CAMEO), compared to not using BaseGraph at all.

There is a singular case of a massive 80% decrease in RMSD (good thing) in a CAMEO target! It’s an n of 1, so obviously take it with a grain of salt, but it perhaps does imply that the utility of Basecamp’s expanded MSA dataset can only be seen with specific proteins. If this is indeed the case, aggregate accuracy of the model will disappoint, but still be massively useful in certain cases! Time will tell if that is actually the case.

Conditional language models enable the efficient design of proficient enzymes

Paper here. Published on bioRxiv in May 2024.

As discussed, enzymes are useful! One way to discover enzymes with interesting biochemical properties is to discover them from nature directly, such as in the paper from earlier. But another way could be to use nature as training data, and generate new enzymes entirely. This is especially salient for enzyme reaction classes which are rare in nature due to not many biophysical processes needing it, so data mining is insufficient to discover them.

Other enzyme generation methods are a bit limited in this conditional generation aspect, requiring fine-tuning on enzyme classes a user is interested in. Ideally, users could specify in a reaction category amongst hundreds of possible ones, and the used model would be general enough to grasp how to generate such enzymes without requiring fine-tuning. This paper wrote about this exact application.

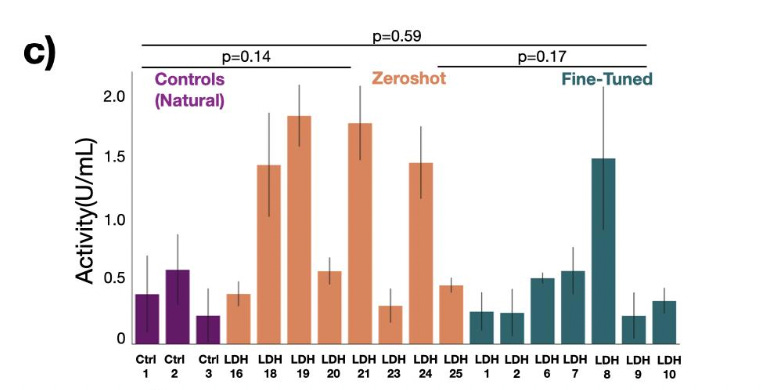

What did they do? Trained a transformer model on UniProt data that accepts a desired enzyme class and generates corresponding sequences of it. They use this to create 20 zero-shot carbonic anhydrases, of which 2 have low sequence identity to natural anhydrases and comparable enzymatic activity. So it’s good from a zero-shot perspective.

While ZymCTRL doesn’t require fine-tuning, they also demonstrate the utility of their own dataset (BaseGraph) by finetuning their model on it. Specifically, a class of enzymes called lactate dehydrogenases. They show that the fine-tuned generated enzymes are of generally higher quality (better functional enzymatic activity) compared to zero-shot generated enzymes.

One comment: They only give enzyme fine-tuning results for a model trained on their own dataset, with no comparisons to fine-tuning on public sources! Lactate dehydrogenases are well-studied enzymes, and undoubtedly exist in public repositories to some degree. These results are technically impressive from a raw scientific angle, but it does remain to be seen whether their private dataset (their main value add) is genuinely better than the public sources.

How do they make money?

Okay, so we’ve gone through their product and released research, both of which seem promising. But how do they actually make money from any of this? As of today, it seems to primarily be by selling enzymes.

They already have several partnerships in this direction for industrial manufacturing, such as enzymes that break down plastic waste and enzymes that are better catalysts for small-molecule manufacturing, amongst a few others. It unfortunately isn’t discussed whether these enzymes were generated or found in their dataset. There is one case I’ve found where the partner explicitly did license an enzyme from Basecamp (and not just form a partnership with no clear outcome), implying that at least someone found the enzyme useful. Unfortunately, I’m not finding any dollar amounts here, so it’d be hard to gauge how valuable this is. On a macro level, the enzyme market size is pretty immense (and growing!), so as long as Basecamp continues producing enzymes people want, this feels like a decent model.

Are they exploring anything else? Curiously, Philipp mentioned that the industrial usage of enzymes is actually minor compared to what their real focus is in the enzyme space: genetic engineering. Specifically, the discovery of large serine recombinases (LSR’s), which are enzymes that facilitate precise genome editing. This was curious, because this doesn’t appear in public articles about them at all! All I could find was a single article about them discovering these LSR’s in their dataset, very curious about the partnerships they set up to take advantage of this. This is an excellent example of how Basecamps edge is not simply the amount of data they collected, but how they collected it as well; the majority of the discovered LSR’s are the result of long-read sequencing, which is relatively uncommon in public metagenomic databases.

There is one other possible play here: selling the data directly to ML x biology companies or labs. But it doesn’t seem like something Basecamp is actively investing in. Another discussion with Philipp confirms this — they believe there is far much more value in directly exploiting their own data rather than selling it to others. In many ways, this is a huge green flag, it signals strong conviction in the value inherent in their dataset, rather than chasing marginal improvements in improving other companies models using that dataset.

Selling data directly to ML x biology companies is still an interesting idea though. If Basecamp did go this direction, how valuable would it be? Well, there’s some upfront work. It will likely take a few more papers establishing the raw utility of the diverse sequences for researchers to really want to use them, the papers we’ve talked about make the dataset itself feel of marginal value to generalized protein models. Past that, there seem to be only two sequence heavy ML x biology companies, Profluent and Evolutionary Scale, which feels like a reasonably small market. Perhaps Basecamp could also sell the data directly to universities for them to use in labs? Again though, likely more convincing will be needed.

Because of this, it feels like an excellent move to eschew the data-as-a-service business model!

Either way, I think the really interesting part of the whole business model is the moat. Not necessarily the sequence moat, which does exist, but is obvious. The far more curious one is the legal moat.

See, you can’t just up and take genetic material from where you want in the world, package it up, and sell it. You have to also comply with an international agreement called the Nagoya Protocol, a 2010 international agreement between 136 members of the UN and EU. Within it, it stipulates that countries have sovereign rights over their genetic resources. This means that any company wanting to commercialize products based on genetic resources isolated from plants, animals, or the environment, must obtain prior informed consent from the country of origin and negotiate mutually agreed terms for the sharing of benefits arising from their use.

Why does it exist? To ensure fair and equitable sharing of benefits from genetic resources, creating a framework that protects biodiversity-rich nations and indigenous communities while facilitating responsible scientific and commercial use of these resources. It’s a good thing!

It’s also incredibly annoying. More importantly, it is annoying and vague! A 2017 paper laid out the bureaucratic challenges with complying with the Nagoya Protocol, another paper commented on how it cripples global biodiversity research. There’s also this really interesting legal breakdown of how compliance with the Protocol actually works and it seems…painfully complicated.

How much does this matter in practice? I reached out to a friend who, in a past life, was involved in entomology research (the study of insects) to discuss this. Entomology is a fairly biodiversity-heavy field, requiring genetic samples from all over the world to conduct interesting research. I asked him how much the Nagoya Protocol practically interfered with his and his colleagues work, and he had this to say:

Yeah, [the Nagoya Protocol] is a big obstacle, at least in museum and collections-based work. When it first came and for years after, the bureaucratic burden was huge and a lot of research just stopped because there weren't any staff members who could handle it, until admins started hiring specifically for dealing with it (and since museums and collections are non-commercial, that's budget that was usually taken out of research budgets, so knock-on effects).

Alternatively, curators had to deal with the paperwork, meaning less time to do their real jobs. And of course permits were much more severely restricted, meaning no more sampling and collecting from biodiverse countries that are severely understudied. Some of those wouldn't even share genetic data.

So it slows a lot of research down, or even completely prevents it (or it forces researchers to have to travel to every country to study specimens locally, which is a huge blow to these tiny budgets and is often paid out of pocket)

[The Nagoya Protocol] is viewed pretty much negatively among the people I know, it's just too against the spirit of open science and collaboration

Here’s the legal moat that Basecamp Research has: every sample they have ever collected is Nagoya Protocol compliant.

Basecamp Research wants to make it easier for researchers to gain access to valuable genetic data without violating any ethical considerations. Every sample they collect is compliant with the United Nation's Nagoya Protocol. Their goal is to make the Nagoya Protocol work for all parties: they do the heavy lifting when it comes to establishing agreements so that when companies come to them for assets, they do not have to worry about infringing national and international biodiversity laws: “We have partnerships in 18 countries with biodiversity hotspots,” said Oliver. “These are benefit-sharing arrangements where we give back: we build research capacity, do training and develop labs in those countries.”

Building up this same network from scratch seems like it’d be incredibly challenging. As it stands today, Basecamp owns the levers to access mass scale, standardized metagenomic data in a way that is convenient, diverse, and legal. They occupy a corner of the market that’d be difficult for anyone else to touch in a similar way. And while the US has not signed the Nagoya Protocol and thus doesn’t need to comply with it, pretty much every other high-biodiversity area of the world has (e.g. Brazil, Indonesia, India, and so on).

What bets is the company making?

Overall the state of the company feels deeply promising! Interesting product and a moat. What else?

All companies, by virtue of existing at all, are implicitly making bets on where the future is heading. Basecamp is no different. Let’s end this essay by going through them!

Here are the bets I’m seeing, ordered from riskiest to least risky:

There is still plenty of useful metagenomic diversity to explore. This is the strongest bet I believe Basecamp is making. And I doubt anybody really knows the answer as to whether this is correct. The fact that there is extant unexplored diversity is irrefutably true. But whether it’s useful? It’s a very unknown-unknowns thing. It may very well be the case Basecamp’s current set of sequenced biomes cover most of the desirable metagenomic space, and further sequencing efforts will cost them money with little marginal return. A paper covering how much better their models get year-after-year of sequence collection would be super useful here! For what it’s worth, Philipp strongly believes that that surface has yet to even be scratched w.r.t. useful microbial diversity.

Sequence-only approaches are sufficient to discover interesting things. Their focus on pure DNA may lead Basecamp to ignore potentially other interesting facets of environmental microbes. This is a risky bet in my opinion. But I also believe that, given Basecamp’s legal moat, they are well equipped to deal with it. Just because they are focused on metagenomic data does not mean they cannot eventually collect diverse metatranscriptomic and metaproteomic data as well. Indeed, Philipp mentioned that they are internally experimenting with collecting microbial data beyond DNA alone.

Evolutionary genetic space contains most of the useful proteins. Not having to rely on what evolution crafted is one of the big draws of de-novo generative models. And, while Basecamp has their own generative models, they are clearly placing a bet on evolutionary related proteins being the most physiologically useful in practice. This is again an unknown-unknowns thing, Basecamp clearly has historical precedent on their side. A dizzying amount of useful therapeutics and lab tools have come from the natural world, and there’s no reason to expect it’ll stop. But this is a very low risk bet because it is very much a bet they can deviate from at any point in time! If, for example, their customers start to demand enzyme catalysis rates beyond what nature has to offer, there are few others in the world who have a better dataset to train de-novo enzyme generation models, given that such models can typically generalize beyond evolutionary space.

The Nagoya Protocol isn’t going away. This one feels extremely safe to assume. International agreements rarely just disappear, especially given how relevant the agreement in this instance is to global biodiversity. Basecamp’s legal moat will likely stay intact.

That’s about it! Very much looking forwards to what this company ends up doing in the future.

Excellent post!

Thanks for this! Looking at this from an outside perspective, it looks like so far their revenue and market opportunity comes from straight licensing of enzymes found in nature (https://matthey.com/media/2023/basecamp-research-partnership), but I'd bet that this is a limited business case. The market study you link on enzymes mentions deals like Roche licensing a DNA ligase, but I really doubt you're going to find a therapeutically useful DNA ligase hanging out in an ice crevice in the Antarctic.

I don't think protein generation as a business is as easy as they are making it out to be. A neat enzyme is a good first step, but there's so much more work to turning it into a business. To take your PCR example, none of the discoverers of Taq DNA polymerase made any money off of their discovery, mainly because the process of PCR was needed to make it useful. And developing PCR itself required a ton of extra work outside of just the polymerase, which presumably a company like Basecamp would not be equipped to do.