Some notes: I will be in SF next week, and am co-hosting this event with the wonderful convoke.bio from 6:30pm-8:30pm on June 24th. Location TBD, but it will be in SF! You should come! Also, I very bravely chatted with Endpoints News a few days back about AI in the life-sciences. Finally, extremely grateful to Shilpa Pothapragada for both inspiring + reviewing this essay.

Edit on June 20th 2025: Lots of interesting perspectives/corrections have been given in response to this article, so I decided to wrap up the most interesting 8 of them here.

Introduction

There are several diseases that are canonically recognized as ‘interesting’, even by laymen. Whether that is in their mechanism of action, their impact on the patient, or something else entirely. It’s hard to tell exactly what makes a medical condition interesting, it’s a you-know-it-when-you-see-it sort of thing.

One such example is measles. Measles is an unremarkable disease based solely on its clinical progression: fever, malaise, coughing, and a relatively low death rate of 0.2%~. What is astonishing about the disease is its capacity to infect cells of the adaptive immune system (memory B‑ and T-cells). This means that if you do end up surviving measles, you are left with an immune system not dissimilar to one of a just-born infant, entirely naive to polio, diphtheria, pertussis, and every single other infection you received protection against either via vaccines or natural infection. It can take up to 3 years for one's ‘immune memory’ to return, prior to which you are entirely immunocompromised.

There’s a wide range of such diseases, each one their own unique horror. Others include rabies (trans-synaptic transmission), ebola (causes your blood vessels to become porous), tetanus (causes muscle contractions so strong that they can break bones), and so on.

Very few people would instinctively pigeonhole endometriosis as something similarly physiologically interesting, or at least I wouldn’t have. But via a mutual friend, I recently had a chat with Shilpa Pothapragada, a Schmidt Fellow studying at the Wyss Institute at Harvard. She studies better ways to diagnose endometriosis, and, as a result of the fascinating conversation, I now consider the disease one of the strangest conditions I’ve ever heard of.

Honestly, prior to my discussion with Shilpa, I didn’t even know what endometriosis even was, only that it was painful to have and affects women. To judge whether I was simply deeply ignorant, or the disease genuinely didn’t have much mindshare, I took an informal poll amongst a dozen friends outside of the life-sciences. Even amongst cisgender women (!), knowledge of what endometriosis was astonishingly sparse — most people could only say something like ‘that’s a uterus condition, right?’, and a sum total of zero people actually knew what the disease entailed.

So I decided to write this essay in an attempt to fix that knowledge gap amongst the small population of people who follow me.

Why is endometriosis interesting?

But, before we get to my points: what actually is the clinical definition of endometriosis?

Plainly put, it is when tissue that resembles the uterine lining, or endometrial-like tissue, grows outside the uterus. The tissue can implant itself in nearby tissues, like the ovaries and fallopian tubes, or even more distal organs like the bladder and bowel. Due to the continuous influx of hormonal growth factors (mainly estrogen), these misplaced endometrial-like cells respond cyclically, just as the normal uterine lining does. They thicken, break down, and bleed with each menstrual cycle, but unlike the uterine lining, they have nowhere to go.

Instead of exiting through menstruation, this trapped tissue and blood accumulates, causing severe pain, inflammation, fibrosis (scar formation), and adhesion between organs. Over time, these repeated cycles of inflammation and fibrosis may lead to permanent structural changes within the abdomen and pelvis, contributing to chronic pelvic pain and infertility.

To segue into the first interesting aspect of the disease, how did the tissue get there in the first place? What caused it to be trapped? Well, it’s a curious question, because…

The primary hypothesis of why it exists is not complete

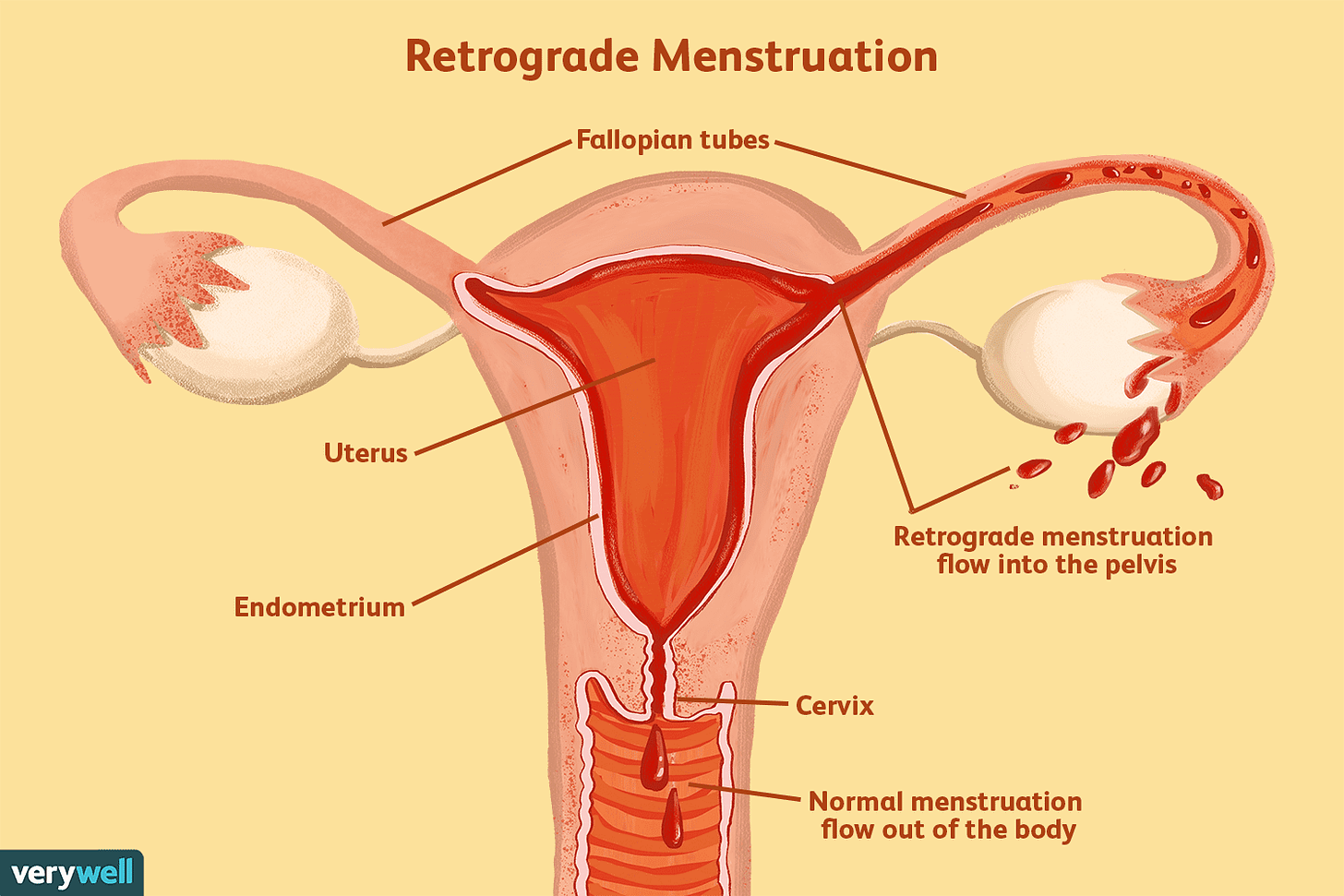

Retrograde menstruation is perhaps the most culturally dominant theory as to why endometriosis occurs at all, first proposed by gynecologist John Sampson nearly 100 years ago. The theory is straightforward: during menstruation, some sloughed-off endometrial cells flow backward through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity instead of outward through the cervix. Once there, these cells implant themselves, continue growing, and become the endometrial-like tissue characteristic of endometriosis.

It’s a clean and simple idea, one that is repeated by gynecologists constantly. I don’t have a great mental model for what this looks like, so I found the following picture helpful:

If you look this theory up on endometriosis forums, most patients generally consider it to be unilaterally false. But there is some decent evidence for it being at least partially explanatory. A strong piece of proof for it is that women with obstructive Müllerian anomalies, or uterine deformations that can lead to more retrograde menstruation, have a higher risk of endometriosis compared to women with no abnormalities.

But, despite how often the theory is repeated amongst doctors, it cannot explain all endometriosis cases. Why not?

For one, retrograde menstruation occurs in between 75-90% of women, most of whom never go on to develop endometriosis. Keep in mind that obstructive Müllerian anomalies occur in 1-5% of the population, and endometriosis rates are about 10% of the reproductive age women. And endometriosis itself is almost certainly under diagnosed! We’ll discuss the insanity of this 10% number later, but, suffice to say, while retrograde menstruation may play some role in the development of the disease, it cannot cover the full scope of cases. To be fair, Müllerian anomalies are also underdiagnosed, but it feels unlikely to make up the gap.

Two, endometriosis comes in multiple forms, some of which stay localized to the pelvic region, yes, but endometriosis can occur in absurdly distal regions as well. Where else? Literally everywhere. Type ‘[an organ system] + endometriosis’ into Google and you’ll find at least one case report of it happening there. The gastrointestinal tract, the lungs, and, insanely enough, the brain as well. How could backwards flow of uterine blood explain that?

And three, perhaps most damning of all, is that endometriosis has been found in people who have never menstruated at all: such as premenarchal girls between the ages of 8.5-13, women who genetically lack a uterus, and even cisgender men. This last bit is a particularly rare phenomenon, with only 16 cases reported in the literature circa 2018, but it conclusively exists. One interesting note: all 16 of the male endometriosis patients likely had increased estrogen levels, either due to liver cirrhosis (which leads to a decreased ability to break down estrogen), high-dose estrogen therapy for prostate cancer, or obesity. You may instinctively wonder: does endometriosis also occur in transgender women on hormone replacement therapy? Unfortunately, I was unable to find any evidence of this, but I chalk it up to the relatively small number of people in this demographic having a similarly rare condition.

So what does cause endometriosis? Well, we’ll need a theory that deals with multiple issues at once:

Accounts for endometriosis occurring in regions far from the pelvic region.

Rules out retrograde menstruation hypothesis.

Accounts for endometriosis being a very heritable disease.

Rules out purely environmental explanations (e.g. greater air pollution, microplastics, etc).

Accounts for endometriosis occurring, albeit very rarely, in non-menstruating individuals.

Rules out any theory that requires the endometrial lining to exist at all.

It’s a tough set of criteria. And a lot of theories have spawned to explain it.

There’s the embryonic rest theory, which blames the condition on pockets of endometrial cells that never migrated properly during embryogenesis and instead remained dormant in various tissues, only to be activated later by hormones like estrogen. This explains the disease occurring in cisgender men (as everyone starts off with progenitor cells capable of differentiation into endometrial cells) and cisgender women who theoretically should lack a shedding endometrial layer. But, unfortunately, it fails to account for why 90% of all clinically visible endometriosis lesions still cluster on the pelvic regions/ovaries rather than turning up at random sites, and why onset tracks so tightly with the start of the menstrual cycle and mysteriously improves during pregnancy.

A cousin to this is the coelomic metaplasia theory, which asserts that the coelomic epithelium (the layer of cells that lines the surfaces of all abdominal organs) retains the plasticity to transform into endometrial-like tissue under specific stimuli, such as hormonal signals, inflammation, or genetic predisposition. But this too suffers from similar issues; if this transformation can happen anywhere there is coelomic epithelium, why is it almost always clustered in the same anatomical zones, and how can it appear elsewhere?

And there are so many more theories beyond this. Still others blame it on immune dysfunction, entirely somatic mutations, and even bacterial contamination.

So…which one is true? Unfortunately, as is often the case with biology, the answer may very well be ‘a combination of all of them’. As you go from papers from the 2010’s to the 2020’s, there is increasingly more and more hesitance in ascribing a single cause to the condition. Instead, it is likely that endometriosis itself results from a general process of heterogenous events. I’ll give the general take I’m seeing people swirl around. There isn’t a great paper covering the following few paragraphs, but rest assured that it isn’t mine, but rather a synthesis of multiple review papers I’ve gone through.

First, there must be a seed: a founding cell with latent endometrial potential. This can be embryonic stem cells that never completed Müllerian migration or circulating multipotent stem cells (which accounts for cis men/non-menstruating women cases), but, more often than not, it will be likely be endometrial stem cells found in menstruation blood (accounts for cis women).

Next, the seed must reach the correct ‘soil’ for growth to occur. Retrograde menstruation would deposit endometrial stem cells in the ideal place: the pelvic peritoneum, which is bathed in the estrogen-laden menstrual fluid that pushed the seed there in the first place. That’s right, we’re back to the retrograde menstruation theory! But unlike that theory, embryonic stem cells or circulating multipotent stem cells also have the opportunity to result in endometriosis, but they only develop into lesions under unusual conditions; such as hormonal therapy or chronic inflammation (e.g. cesarean scars). This explains a lot of things! The rarity and the distribution of extra-pelvic endometriosis, why increased rates of retrograde menstruation lead to a higher risk for endometriosis, and why high-estrogenic conditions usually co-occur alongside endometriosis in people who theoretically shouldn’t develop the disease.

Finally, the seed must survive, adapting its local environment to suit its needs. There is evidence that endometriosis lesions can secrete immunomodulatory factors that help them evade immune clearance, release angiogenesis factors that promote blood supply to them, and tamp down its responsiveness to progesterone levels as to prevent natural hormonal suppression of growth. How does it do all of these? Simple: the acquisition of somatic mutations and epigenetic changes that reprogram the lesion’s cellular behavior. Which explains why people have observed so many genetic anomalies in endometriosis lesions, and also why simple retrograde menstruation isn’t alone enough to cause endometriosis.

And yet, we still haven’t explained everything about the origins of endometriosis. What causes circulating/latent stem cells to transform into endometrial-like cells? Why does spontaneous regression of endometriosis sometimes occur? Why do some endometriosis lesions remain stable for years? Why don’t all genetically or hormonally predisposed people develop it?

All unclear! Still much work left to do to account for all of these.

And, you know, upon reading about the above pathogenesis of endometriosis, one may immediately remark on how similar it feels to another condition…

It is nearly equivalent to cancer

Seeds? Somatic mutations? Spreading? Spontaneous start and stop?

That…sounds an awful lot like cancer, doesn’t it? And not just the typical, innocuous gynecological disease that one may initially assume endometriosis is.

If you aren’t yet convinced, let’s return back to the seed metaphor we were using in the last section. For a seed to survive, it must manipulate its immediate environment, happening upon somatic mutations that allow it to do so. Very cancer-y sounding! And, curiously enough, many of the mutations that cells found in endometrial lesions are identical to those found in cancerous tumors.

A Cell paper from 2018, which compared somatic mutations between normal endometrial tissue and endometriosis tissue had this to say:

While we were preparing to submit this manuscript, Anglesio et al. reported that 21% of the lesions in patients with deep-infiltrating endometriosis harbored somatic mutations in ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, and PPP2R1A. Our results corroborated their findings in a larger cohort of subjects with a more common type of endometriosis….

For context, all of the named genes are recognized as known oncologic mutations.

Of course, clonality should be considered when assessing results like this, as in, what fraction of the assessed cell population had the mutation? If it’s a low proportion, it is background noise. If it’s high, it may be what is keeping the cell population afloat. And indeed, endometrial tissue, on average, had much higher fractions of KRAS and PIK3CA mutations than normal endometrial tissue.

We could push this even further and ask the question: does a higher mutational burden of these genes cause endometriosis to be even more aggressive, just like how it does for cancer aggressiveness? One paper studied this, though only through the lens of KRAS, and the answer was pretty clear: yes.

KRAS mutation presence was higher in subjects with deep infiltrating endometriosis or endometrioma lesions only (57.9%; 11/19) and subjects with mixed subtypes (60.6%; 40/66), compared with those with superficial endometriosis only (35.1%; 13/37) (p = 0.04). KRAS mutation was present in 27.6% (8/29) of Stage I cases, in comparison to 65.0% (13/20) of Stage II, 63.0% (17/27) of Stage III, and 58.1% (25/43) of Stage IV cases (p = 0.02). KRAS mutation was also associated with greater surgical difficulty (ureterolysis) (relative risk [RR] = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.02–2.11) and non‐Caucasian ethnicity (RR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.47–0.89). Pain severities did not differ based on KRAS mutation status, at either baseline or follow‐up. Re‐operation rates were low overall, occurring in 17.2% with KRAS mutation compared with 10.3% without (RR = 1.66, 95% CI: 0.66–4.21).

In conclusion, KRAS mutations were associated with greater anatomic severity of endometriosis, resulting in increased surgical difficulty. Somatic cancer‐driver mutations may inform a future molecular classification of endometriosis.

Given all of this, it is worth wondering in what manner endometriosis is genuinely distinct from cancer. Why don’t we simply consider the two one and the same? Is there some obvious dividing line between endometriosis and tumor that I have simply left out?

No. There really is a striking level of similarity between the two.

Of course, I am not the first person to draw this connection between endometriosis and cancer, far from it. One paper from 2017 titled ‘Endometriosis: benign, malignant, or something in between?” had this to say:

Should endometriosis be considered a ‘benign’ neoplasm, which harbors oncogenic driver mutations, along with the capacity for invasion and potentially for distant metastasis? Although exhibiting classic hallmarks of cancer, it is not lethal, is morphologically normal, and does not form an expansile tumor mass. The recent findings invite us to revisit our notions of what constitutes cancer, and should re-ignite interest in the biology of endometriosis, an entity which could aptly be described as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.”

I’m not the first one to point out how strange this disease is!

But perhaps even comparing this to cancer understates the true horror of late-stage endometriosis. In the absolute worst-case prognosis, lesions can form deep fibrotic adhesions that tether organs to each other: the bladder fused to the uterus, the bowel glued to the pelvic wall, the ovaries fixed in unnatural positions. One commentary paper states this:

It doesn’t take more than a short inspection into the peritoneal space of a patient with widespread superficial or deep infiltrating endometriosis to understand that this is not the appearance of a usual benign disease. It’s not uncommon that a surgeon walks out of the operating theatre after a long and exhausting endometriosis case, saying: “This is worse than metastatic cancer”!

But at least with late-stage cancers, there are some miracles that can be accomplished. After all, the birth of cancer immunotherapy came from finding that, in rare cases, patients with late-stage tumors could see a complete and miraculous remission, as if entirely by magic, all through their immune system. And if a patient's immune system could do this once, even rarely, then perhaps it could be trained—or unshackled—to do it more reliably. So we got checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T therapy, and so on.

For patients who have endometriosis, is there anything remotely analogous?

There is no (real) cure

Unfortunately, no.

Currently, there are two routes for endometriosis treatment: noninvasive chemical treatments, and invasive surgical treatments.

In the former case, the primary strategy revolves around hormonal therapy. The logic is simple: starve the lesions of the chemical cues they need to grow and cycle. Oral contraceptives are used to flatten the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle, progestin mimics to induce an atrophic state in the endometrial-like tissue, and, in short doses, GnRH agonists to induce a reversible state of complete estrogen suppression. There are other treatment paths too, but these are the most commonly-used ones.

In the latter cases, usually for endometriosis that is either resistant to hormonal therapy or has progressed to the point of causing anatomical distortion, organ dysfunction, or intolerable pain, direct surgical intervention is used. The goal is twofold: remove/destroy visible lesions, and restore normal pelvic anatomy that have become fused together through endometrial-tissue-like overgrowth.

Neither of these do anything to actually cure the disease. I want to be fair and give the necessary nuance to that statement, because it is a strong one to make, but I want to be clear. What they both do is management of endometriosis. But they do not represent a cure in any functional capacity.

In the case of hormonal treatments, the endometrial tissue doesn’t starve, not really. There are cases where hormonal treatments do genuinely reduce the size of a malignant entity, such as in estrogen-dependent breast cancer. But this is not the case for endometriosis lesions. One review paper found that while hormonal therapy helps slow progression in some patients, there is minimal evidence of change in the size of endometrial lesions over months of continued therapy. Moreover, oral contraceptives do not seem to stop the expression of angiogenesis factors within endometrial lesions, and may in fact somehow accelerate it. And if a patient ever stops the hormone therapy, relapse is the norm; one study found that a majority of patients saw symptom-recurrence within 5 years after finishing a year-long cycle of GnRH-agonist therapy.

The case for surgery isn’t much better. While surgery certainly, on average, helps with endometriosis-associated pain, it isn’t curative. The numbers obviously depend on a lot of different factors, but 5-year post-operative recurrence rates are between 20-45%, and the 8-year rate is squarely in the 40% range. Which maybe doesn’t sound terrible, but consider that endometriosis surgeries aren’t risk free at all, with roughly 1% of patients developing a major-post operative complication (e.g. bladder injury, bowel injury, vaginal dehiscence, etc). Mildly good news is that it doesn’t seem like that development of these complications go up based on whether you’ve had the surgery in the past.

There are options outside of hormonal therapy and surgical operations rising, but they are largely still in their infancy. There’s dichloroacetate, which, interestingly, is also a promising drug for cancer for the same reason it works for endometriosis. Both cancer and endometrial tissue seem to display the same unique form of cell metabolism (the Warburg Effect), which dichloroacetate disrupts. There’s also cabergoline, a drug meant for Parkinson’s disease that also coincidentally hinders angiogenesis, and has been shown in at least one randomized trial to reduce pelvic pain caused by the disease. There are other burgeoning non-hormonal chemical treatments being developed, but, again, none of them seem to be in active use.

This all said, having no curative procedures at all, and only management ones, isn’t the worst thing in the world. After all, that’s the status quo for HIV! And that disease went from a death sentence to something that just requires a simple pill per day to keep it at bay, no other functional impacts. It can’t be cured, but that doesn’t matter. The patient's life is basically the same either way.

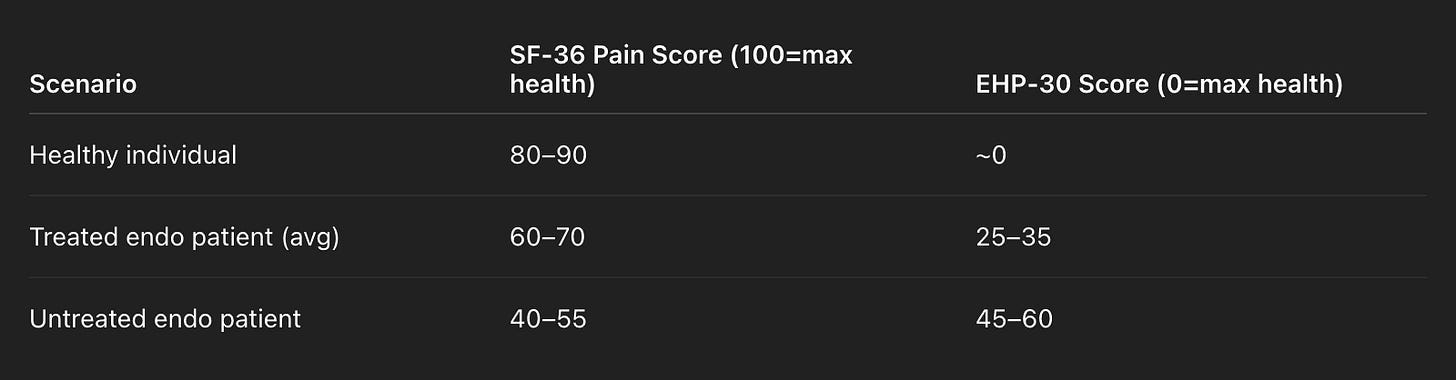

Is that the case for endometriosis? If you follow the currently recommended set of hormone therapies and surgeries (if needed), can a patient return back to their pre-disease state? In one of the most comprehensive review papers I found, they examine that exact question, combing through 139 past studies to come up with an issue. And, generally speaking, the answer is no. The (heavily simplified) results are here:

There are certainly improvements with the currently approved treatment plans, but the situation is a fair bit worse here than it is for HIV. There is a long, long way to go for endometriosis to become a ‘background’ chronic condition, rather than one that continues to cause a lowering of quality-of-life even when treated.

Well, this all said, endometriosis isn’t alone here. Lots of diseases also have enormous, chronic impacts on quality of life and have little in the way of dependable treatment. Cancer of course, but also Alzheimer's, Crohn’s disease, ALS, and so on.

But within this observation lies perhaps the most curious part of endometriosis…

There are few diseases on Earth as widespread and underfunded as it is

One potential way to assess how overlooked and widespread a disease is is by considering the ratio of ‘DALYs’, or Disability-Adjusted-Life-Years, to the amount of NIH funding. Or, Dollars:DALYS.

The former is an indication of how institutional focus is being placed on the disease; more money, the more attention. There are obviously money sources outside of the NIH, but the NIH remains the single largest public funder of biomedical research in the world (at least for now…), and its budget choices set the tone for scientific priorities across academia and industry.

The latter is an indicator of how severe and widespread the disease is, with a simple calculation: DALY = YLL + YLD, where YLL (Years of Life Lost) is years lost due to premature death and YLD (Years Lived with Disability) is years lived while disabled. Keep in mind that this is years across some given population, not in one person, which also gives an indication of how widespread the condition is. Of course, DALYs are a limited metric given how subjective ‘disability’ is, but it’s a helpful starting point.

Thus, if Dollars:DALYs is high, that implies that funding is either proportionate to suffering, or is perhaps over allocated to. If it is low, the funding is almost certainly not enough. This is obviously a fuzzy metric, since research doesn’t necessarily go faster just because you throw more money at it, but it is helpful as a data point.

To keep things consistent, let’s work at the order of millions of dollars and DALYs per 100k people, since that is how they both are typically reported. Let’s also focus on chronic conditions, since that is where DALYs are most relevant. Finally, we can pull NIH funding numbers from here, and find the DALY counts from review papers.

On the highest end, Alzheimer's received $3538M in funding in 2023, and caused 451 DALYs per 100k people worldwide. So, 3538:451, or 7.8.

Then Crohn’s Disease, which has the ratio 92:20.97 (4.3).

Slightly lower is diabetes, 1187:801.5 (1.4).

Close to it is epilepsy, 245:177.84 (1.6).

Finally, near the bottom of the list is endometriosis, 29:56.61, or .5.

Quite bad. That said, endometriosis isn’t alone in being deeply underfunded. Another condition with an even worse ratio is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which lies at 148:926.1, or .15. Why COPD? Mostly given its stigma as a self-inflicted disease. But there is some reason to believe that the true ratio for endometriosis is even worse than what they appear to be on face value.

Why? Diagnosis lag.

Endometriosis takes, on average, 7–10 years to be diagnosed after symptom onset. This is not due to the subtlety of the condition; patients often present with debilitating pain, irregular bleeding, gastrointestinal symptoms, and infertility. But diagnosing endometriosis is difficult, the gold standard for it being an invasive and expensive procedure that requires general anesthesia: laparoscopic surgery. While noninvasive imaging (like ultrasound or MRI) can sometimes detect large lesions, many forms of endometriosis, particularly superficial or deep-infiltrating types, are not easily visible this way. As a result, a patient must often endure years of symptoms before someone is willing to escalate their care to diagnostic surgery. Because of this, it feels deeply likely that many endometriosis cases simply never enter official registries, making the total burden likely massively undercounted in global DALY calculations.

Notably, this is unlike most other diseases, even historically underfunded ones, which typically have clear diagnostic criteria that can be confirmed through inexpensive blood tests, imaging, or clinical presentation alone. For example, COPD can be easily diagnosed via spirometry: just blow into a tube.

Given this, how should we update our Dollars:DALYs ratio for endometriosis? One way would be to ask the question: how many cases of endometriosis are currently undiagnosed? A 2014 study answers this question, albeit limited to a specific region in Italy, by actively searching for endometriosis in a sample of 2,000 premenopausal women who had visited a GP for non-gynecological reasons. Of these, 28 had already been diagnosed with endometriosis. Using a symptom-based questionnaire and surgical follow-up, the authors discover 37 more cases amongst the 2,000 women. In other words, 60%~ of endometriosis cases would not be discovered if there was no active search for them.

In the absolute worst-case situation, this should lead us to bump our DALYs for endometriosis up by 60%. Starting with a base DALY of 56.61 per 100k people, this leads us to 141.52.

Thus our ratio becomes 29:141.52, which is a dismal .2, close to that of COPD.

Now, again, that is a worst-case calculation, where the ‘density’ of DALYs in the ‘undiscovered endometriosis’ patient population is identical to that of patients with the diagnosis. This may not be the case, but it’s hard to tell from the literature alone. One study notes that diagnosis is slowest when symptoms are vague or non-disabling, potentially implying that this undiscovered set of endometriosis would yield fewer DALYs. On the other hand, one could imagine the DALYs being higher for some fraction of the undiagnosed condition if the lack of hormonal or surgical management leads to more severe complications down the line.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a remarkable disease. It is something that, despite being studied for centuries, has eluded an understanding of its origins, has an uncanny resemblance to cancer, and lacks any effective curative or management methods. Yet, it stands almost entirely alone in terms of how little funding the condition receives relative to the absolute number of lives it irrevocably alters for the worse: 10% of reproductive age women (or 190 million) worldwide, with only $29M earmarked for them.

Understandably, characterizing any disease as ‘interesting’ runs the risk of seeming flippant. Especially given how intensely emotional the impact of it on patient lives can be: chronic pain, infertility, and life-altering disability. This is not my intention! Here, I use ‘interesting’ as a way to convey a sense of unexpectedness. Many aspects of endometriosis are deeply unexpected. And, perhaps more practically and actionably for readers, it is unexpected in ways that are surely fertile ground for more research.

Of course, it’s certainly a hard disease to tackle. But so are cancer, Alzheimer's, and HIV, all of which have inspired generations of scientists to feverishly work towards understanding. This is partially due to how high the expected impact of such research would likely be, but it’d be rewriting history to not also mention how deeply interesting those conditions were to the people studying them! Talk to any oncology researcher about pancreatic cancer, and they will mention the awfully high death rate, but will also light up when discussing the strangely dense stromal microenvironment that seems to shield it from treatment.

The fascination is inseparable from the fight. And it feels like very few people have tried to cover the fascinating part of the disease, only the fight.

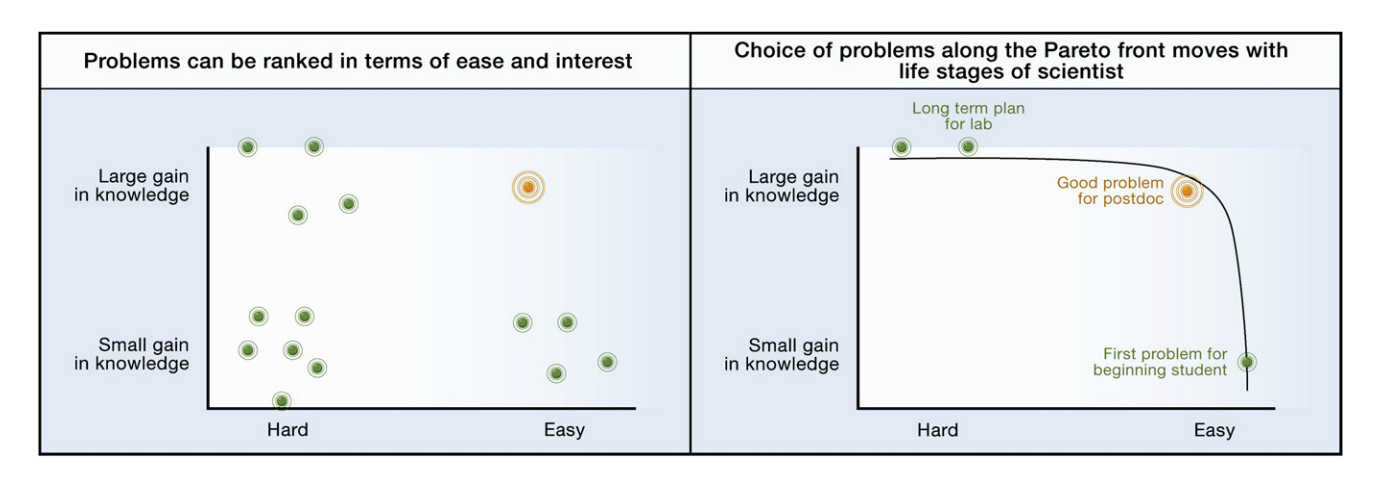

I hope, in this essay, I have convinced you that endometriosis is an interesting condition. And, if you are in a position in your life to do so, it may be worth your energy to work on it. In a 2009 essay written by Uri Alon, a well-known systems biologist, he discusses what makes for a scientific problem worth studying. He comes up with the following graph:

It is obviously impossible for me to state for certain that research into endometriosis will surely result in a large gain of knowledge if more attention, resources, and money is poured into it. But, given the relatively premature state of things in this field, it’s difficult to imagine otherwise. Not a bad bet to make!

You may be interested in myalgic encephalomyelitis, which had an estimated disease burden in the US of 0.7m DALYs [1], and NIH funding of $13m this year. That would put the ratio at 0.06, far below the other diseases you've listed. The disease burden estimate is pre-pandemic, and ME/CFS is one of the more common sequeala of covid, so the ratio is likely worse again.

ME/CFS is also incredibly interesting for its hallmark symptom - a highly unlinear response to exertion. Mild patients can often go about parts of their day to day life just fine, but if they hit an exertion threshold they can be bedbound for weeks. Severe patients are permanently bedbound and processing light is beyond the exertion threshold for some.

Mitochondrial dysfunction [2] is thought to be central to the disease. A large scale (n=18k) GWAS study will be reporting in the next two months [3]. Strong evidence of autoimmunity have been found in a subset of patients (hot off the press, from a recent conference [4]).

[1] https://oatext.com/Estimating-the-disease-burden-of-MECFS-in-the-United-States-and-its-relation-to-research-funding.php

[2] https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physiol.00056.2024

[3] https://www.decodeme.org.uk/

[4] https://events.mecfs-research.org/en/events/conference_2025/videos/jeroen-den-dunnen-autoimmunity-cause-mecfs

Fascinating article, thank you. I'm one of the many women who know of endometriosis, but couldn't say what it was except "tissues growing where they shouldn't" - despite having a colleague suffering from severe endometriosis and booked for surgery.

Had never heard about the similarities to cancer before. Do we ever see malignant cancers (as in life-threatening) emerge from ectopic endometrial tissue? (Apologies if this is mentioned and I missed it!)