Bubble Tanks is a Flash game originally released on Armor Games, a two-decade-old online game aggregator that somehow still exists. In the game, you pilot a small bubble through a procedurally generated foam universe, absorbing smaller bubbles to grow larger, evolving into increasingly complex configurations of spheres and cannons. Here is a reasonably accurate video of the gameplay, recreated in beautiful high-definition:

Bubble Tanks was first released in 2007, with a sequel out in 2009, and another sequel in 2010. Back when I first played it as a child, I was convinced, absolutely convinced, that there was someone in the world whose entire life was nothing but Bubble Tanks. This person—and I took it on faith that they were real—woke each morning and immediately, before coffee, before the basic animal functions of evacuation and sustenance, played Bubble Tanks. They posted on obscure forums, arguing bitterly over tank builds and bubble physics with three other people who had the same devotion. I knew that their room was disgusting, repulsive. This was essential to the vision, that their stained clothes lay across their floor, worms crawling over them. They were either skeletal or enormously bloated, monastic asceticism or excess gluttony, one or the other. Bubble Tanks was single-player, so they did not do all this for fame or glory, but for love, or for something even deeper than love. Everything had been sacrificed for this game, and excelling at it would be all that they had ever done, all that they would ever do.

And what if this person were just the start? What if this Flash game became the organizing principle of human civilization? The economy would shift to accommodate. Bubble Tanks coaching would become a viable career path. Parents would discuss their children’s talents at the game over dinner. Political candidates would be asked about their Bubble Tanks records during debates, and one would lose an election after it emerged that he never evolved past the third tank configuration.

Looking back on this fever dream I came up with a decade-and-a-half back, one thing that immediately strikes me is that being creative in such a world must be monstrously difficult. Not because all creativity must be ultimately tailored towards Bubble Tanks enthusiasts—that much is obvious, and is not especially different from creativity in the real world, which must tailor itself towards enthusiasts of human-understandable concepts—but rather because there would be astronomical amounts of Bubble Tanks content already in existence. In the latest stages of this civilization, billions of people have devoted their lives to Bubble Tanks. Millions of them are creative. Hundreds of thousands have genuine talent. Tens of thousands have produced work that is, by any reasonable measure, brilliant. The Bubble Tanks epic poem exists in fourteen languages. The Bubble Tanks symphony has been performed at concert halls on every continent. There are Bubble Tanks novels that have won Pulitzers, Bubble Tanks paintings that hang in the Louvre, Bubble Tanks films that win Oscars. All the obvious ideas have been executed. All the non-obvious ideas have also been executed.

I have wonderful news. You live in the earliest innings of this universe, at the start of it all, just as more and more of the population is beginning to wake up to how great this Flash game is. Even more fortunate for you, it is not only Bubble Tanks that is the object of human devotion. It is everything.

Humanity has been producing art for somewhere between 45,000 and 100,000 years, depending on how generously you define “art” and “humanity.” For most of this period, the constraint on creative output was not imagination, but production capacity. The printing press changed this, then radio, then television, then the internet, and at each stage the volume of creative work accessible to any given person increased by orders of magnitude. Today there are more novels published each year than a human being could read in a lifetime. There are more films, more paintings, more poems, more essays, more podcasts, more YouTube videos, more TikToks, more tweets, more everything than anyone could ever hope to consume.

And as more art is produced, the more we must learn to discriminate. Consider stories. They existed for millennia in the form of epics, religious hymns, folk tales. But with the rise of printing presses that allowed a wider variety of stories to circulate, we were forced to develop something very dangerous: filtering technologies. Genre is a filtering technology. It emerged because no one could read everything, and so readers needed a way to predict whether a given text was likely to satisfy their immediate demands. “Romance” is a promise: there will be a love story, probably with a happy ending. “Mystery” is a different promise: there will be a puzzle, and it will be solved. Both are not really descriptions, but more accurately a contract signed by the author about what the book will do for you. And like all technologies, genre has evolved to become more precise as the volume it must filter has grown. “Sci-fi” was once sufficient. Then it fractured into hard sci-fi and soft sci-fi, into space opera and cyberpunk. Brand awareness is a different filtering technology. Netflix originals have the flavor of something that will likely be decent, but also homogenous, whereas A24 movies have an art-house sensibility with a certain color palette. Each subdivision represents a refinement of the filtering mechanism, a narrower promise to a narrower audience.

Why are filtering technologies a problem? Aren’t they great? We’re getting increasingly good at giving people what they want!

Well, it wouldn’t be an issue if the creative process were limited by human scale, but we’re getting close to leaving that world. I feel pretty comfortable saying that, at this point, LLMs can handle nearly every sufficiently-chunked-up bit of music production, graphic design, video editing, background illustration, character concept art, voice-acting, essay writing, and a lot more. The list extends as far as creative production itself extends, which is to say: everywhere. Every domain that humans have developed aesthetic traditions within is a domain where AI can now perform the components of that tradition with reasonable competence.

One could imagine that in the near future, there will be a new button on your television, one with a sparkle animation. After clicking on it, it will offer you a QR code, politely asking to scan it with your phone. Upon doing so, the button will give you one of the ultimate promises of our new frontier-AI-lab-centric economy: a text box, that will generate a feature-length film using whatever prompt you enter into it. We have arrived. The long march is over. This is the ultimate final utopia that our filtering technologies have been building towards since the first monk started to distribute the Gutenberg Bible. What will we make? What wonders await us?

I suspect the answer is: mostly nothing. Or rather, mostly more of what we already have.

The problem with filtering technologies, one that becomes catastrophic precisely at the moment of their perfection, is that they assume you know what you want. The entire apparatus presupposes a subject who arrives at the interface with desires already formed, preferences already crystallized, a little homunculus sitting in their skull who knows exactly what kind of story it wants to hear tonight. And, to be clear, this actually works remarkably well in the case of a finite set of existing objects. When there are ten thousand, even a hundred thousand films in the Netflix library, the algorithm’s job is merely to surface the handful you’re most likely to enjoy from a pool that already exists. You don’t need to know what you want with any precision. You only need to recognize it when it appears before you, to say “yes” or “no.” Really, the algorithm is not an algorithm at all, but something even more basic: an ophthalmologist. It flips between lenses: better, or worse? This one, or that one? You do not need to understand the properties of curved glass or the anatomy of your own defective eyes. You simply must obediently respond to the question you are asked.

This all breaks down the second you are placed in the driver’s seat, because you do not actually know what you want. How could I make such a proclamation so confidently? I can’t, but I will anyway: what you want most, more than anything else in the world, is stuff that you never realized you wanted.

I realize that this is a tired sentiment, subtweeting the apocryphal Henry Ford line about faster horses. “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” The implication being: I, the visionary, know what you want better than you do. And I, despite the dullness of my audience, will give you the automobile. You would think, reading this essay, that I am making a case for the artist: the sacred figure who reaches into the void and pulls out something none of us knew we needed.

But I am saying something much worse, which is that nobody knows. Not you nor the visionary. The Ford line is wrong not because customers actually do know what they want, but because, if we’re being honest with one another, Ford didn’t know either. It was a happy accident that he later (again, apocryphally, because I don’t think he actually said it) narrativized into inevitability, because that is what popular culture does with fixations that turn out well.

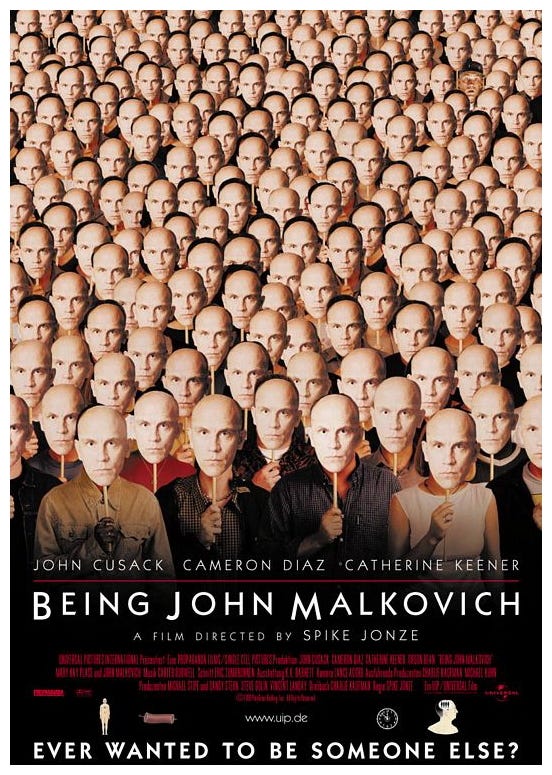

You may guess where this is heading. It’s time to discuss Being John Malkovich.

Being John Malkovich is a nearly two-hour movie, filmed in 1999, directed by Spike Jonze, written by Charlie Kaufman. It stars John Cusack as a failed puppeteer named Craig who takes a job as a filing clerk on the seven-and-a-half floor of a Manhattan office building—a floor with ceilings so low that everyone must walk in a permanent stoop. This detail is never really explained, other than a vague mention of how the original building owner had a wife who was a dwarf, which raises far more questions than it answers, Did he build the entire floor for her? Did she work in this office? Was this an act of love or an insult? By the time these questions have been raised, the film has already moved on, and it is never mentioned again. One day, while filing, Cusack’s character discovers a small door behind a cabinet. He crawls through. In doing so, he finds himself inside the head of John Malkovich, the actor, experiencing fifteen minutes of Malkovich’s life from behind his eyes, before being ejected onto the muddy shoulder of the New Jersey Turnpike.

This is the basic premise, all introduced within the first half-hour of the film. And I have not yet mentioned the chimpanzee.

There is a chimpanzee, who has a reasonable amount of screen time. She belongs to Lotte, Craig’s wife, played by Cameron Diaz. The chimpanzee has intense psychological trauma as a result of being torn from her mother at an especially early age, a fact that was shown entirely through flashbacks. What is the purpose of the chimpanzee being traumatized? It is unclear, because it is never actually a relevant plot point. Why is Lotte taking care of this chimpanzee? Is she an animal therapist? She is not. She works at a pet store, and stores a wide variety of animals beyond just the chimpanzee in her (and John’s) small New York apartment for seemingly no reason at all. Why is the chimpanzee in the film? It seems to be for the sole purpose of a pivotal moment in the film which requires using the chimpanzee’s cage, but this moment does not actually need the prodigiously large cage for it to work, and one could imagine a thousand other more reasonable ways to accomplish the same narrative beat. Despite all this, the chimpanzee is there.

How did Charlie Kaufman, the relatively unknown screenwriter and driving force for the film, even come up with this plot line? In an interview, he says this:

I wrote Being John Malkovich while I was waiting for [the next sitcom] hiring season. My idea was that I would write a script and use it to get work. I had this idea that someone finds a portal into someone’s head, and I had another idea that somebody has a story about someone having an affair with a co-worker. And neither one was going anywhere, so I just decided to combine them.

Oh yes, there’s an affair too. But it gets even funnier. Why is John Malkovich the chosen victim of the portal? Kaufman also gave the answer in a different interview:

I don’t know... I thought it was funny. It’s hard to explain, but I thought it was funny, but not jokey. Because [John Malkovich] is a serious actor, he is a great actor, but there is something odd about him and there is something behind his eyes that you can’t see. And I thought that was a good person for this.

And then I think his name is perfect for the title...

Being John Malkovich is a worrying movie for a filtering technology maximalist, because it is both incredibly good, benefitting from both the insane premise and bizarre details, and is also something that nobody ever asked for. What is the film about really? What is the emotion that it is intended to evoke? It is about identity, I suppose. Also about desire, and the way desire makes puppets of us all. It is about the loneliness of being trapped behind your own eyes. It is also about John Malkovich, specifically, for no other reason other than it being an apparently funny choice. There are a lot of very strange, but ultimately invaluable, stylistic decisions made for this movie, all of which ostensibly made because Kaufman got a kick out of it.

To be clear, I am not saying something like ‘a sufficiently well-prompted AI could not come up with Being John Malkovich’. What I am saying—which actually feels like a pretty defensible viewpoint—is that very few people would ever think to assemble together a prompt to create Being John Malkovich. This opinion does not require any sort of humanist romanticism, or belief in some vague notion in ‘soul’. What it is grounded in, really, is a fairly basic observation about the structure of human desire; which is that desire is not a fixed quantity that exists prior to its satisfaction, but something that is frequently created retroactively by the very thing that satisfies it.

This would not be so bad if it were the only thing happening. The Kaufmans of the world would continue to write their chimpanzees, and the prompt boxes would continue to produce competent variations on existing themes. The end result would simply coexist alongside each other, one being deposited directly in the multiplex, the other in the art-house cinema, each serving its respective demographics.

But there is a second thing happening, and it is happening simultaneously.

Since AI is quite good at producing the art that isn’t too strange, I imagine nearly everyone will be, in due time, happy to hand over their consumption directions over to it. Soon, Suno will produce everyone’s music, Midjourney will make everyone’s phone backgrounds, and so on. Yes, it will be slop, not because it is bad, but because it repeats. Generative models are, by their nature, interested in modeling distributions—trained on everything, they converge toward the most likely areas of their distribution, which means that even when you prompt for something unusual, you are pulling against a gravitational force that wants to return you to the most common areas. The result is that the most common forms of AI output have a flavor, a kind of statistical residue that accumulates across pieces. But most people don’t mind this. They are happy to let the model play the same ophthalmology game with them, because they know they can play that game well, and the results will probably be roughly as good as the last algorithm they played the game with.

And herein lies the problem. Now, there is no longer any reason for the multiplex to exist, because the multiplex is not meant to be genuinely unique, and whatever is not unique can instead be entrusted to our own personal, finely tuned filtering technologies, combined with the infinitely patient AI. Is this bad? Not for the consumer! But it does put the artist in a pickle, because it now means their last remaining way of being seen at all, much less standing out, is to create something like Being John Malkovich. This cannot be easily made by the AI alone, because it does not submit to the ophthalmology game as easily. And creating something like Being John Malkovich is, I imagine, challenging.

Of course, strangeness has always been a useful strategy for art. Even beyond Charlie Kaufman, the greatest artists from the last century were all a bit off. Joan Didion had an unnerving flatness, describing a woman’s suicide from a sexless marriage in the same sentence as a shopping list. Hunter S. Thompson decided that the reporter should be more interesting than the thing being reported on, and shoved his demented, drug-addled brain into everything he wrote. David Lynch made movies in which the nightmarish mysteries refused to be made legible, just rather something you were forced to marinate in during the film. Importantly, nobody was strange in the same way. Didion’s strangeness is one of temperature. Thompson’s is one of proportion. Lynch’s is one of epistemology. What they share is not really a style, but a willingness to identify the thing that everyone else in their field was doing automatically, unconsciously, and to ask: what if I didn’t?

During their times, these people were made rich, famous, immortalized for doing something as brave as this. Things are different today. Now, to be above the crowd is the minimum required to be visible within it.

This is a very stressful situation, and one that all young artists born into the Bubble-Tanks-obsessed universe could likely sympathize with. They too live in a civilization that is utterly consumed with infinite creative production alongside the dimensions that matter—for them, Bubble Tanks—and are forced to produce something underneath a sky that has already seen it all. One can only imagine how strange their work is. Importantly, we occupy the antechamber of this world. What is coming next can be seen from where we stand, and our distance from it is decreasing at a rate that makes projection trivial; five years, ten, and the gap collapses into nothing. There is genuine cause for throat-closing anxiety at this prospect.

You can imagine a rather bleak future is the end result of this. One in which someone sits at their screen, asks their friend.com pendant to create an eleven-season series about a 45-year old Japanese woman and her tsundere relationship with a coworker at the glue factory she works at, and watch the end result with rapt attention. In this hyperatomized future, capital flows only to the frontier model companies and no one else, where nobody has common language to describe the media that they consume to anyone else, since every single piece of media has a singular person as part of both its creation and distribution.

But perhaps something better is possible. Consider an alternative future. This one is exactly same as the first one, with one minor difference: people have moments of intense boredom with what the machine spits out to them, and they decide to go out searching for something else that someone else has made, one that does not taste like something that they, in a million years, could’ve ever come up with themselves. Not because they do not have the technical talent to do so—technical talent is precisely the thing that has been commoditized—but because they lack the particular configuration of a life that would lead someone to write that, to make that choice, to include that detail that seems inexplicable, right up until they encounter it and realize it was obvious all along.

I am increasingly optimistic that the second version is the more likely one, only because it feels as if popular art is being increasingly dominated by the strange, the unmistakable, the ones that have an auteur-esque energy infused into it. To be clear, this is not new. But it used to be a privileged position, something you earned after decades of clawing your way through the studio system, or something you were granted by virtue of being from the correct lineage. Now the privilege has inverted. Now everyone must leave their own distinctive, strange smack on their work, or else disappear entirely. Just take a look around you. The auteur is increasingly colonizing forms of media that once operated on entirely different principles. Substacks, podcasts, technical news; many of the most promising ones today are largely held up by the specific and irreplaceable neuroses of the person producing them. This is strange and new and also very old. It is a return to something like the bardic tradition, in which the story and the storyteller were inseparable.

Of course, none of this is to say that the auteurs are rejecting AI. In fact, the best ones may use it more than anybody else does, as the speed at which production will be demanded in the new world will necessitate it. What makes auteurs so special? It is not the case that they, in their production of the strange, have any claim to particularly fine taste or even soul. In fact, their primary good fortune, often their only one, is that they want something, that they desire to tie great iron chains around some particular, ugly concept and drag it behind them wherever they go, clanking and scraping against the pavement, alerting everyone to their embarrassing presence. The machine has no such desire. It is capable of anything and interested in nothing. And the desire of what is uncommon, it turns out, is the only part of this whole system that struggles to be automated.

You know, most of your followers, including me, are here for your BioML content. And yet here I am, delighted by a read I didn't know I wanted, satisfying a desire I retroactively created. No better way to prove your point.

I'm convinced this is the appeal of cult movie makers like Ed Wood: He *had* to make art regardless of any consequences. Like a salmon swimming upstream, he would do it even if it killed him. Artistic vision yes, but also a terrible burning desire.